“The operational word on the cover of the CATALOG is access. Ultimately, that means giving the reader access from where he is to where he wants to be. Which takes work, work takes tools, tools need finding, and that’s where we come in.”

— Stewart Brand, The Last Whole Earth Catalog, 1971

When we were kids, as long as we were out before cocktail hour, my sisters and I had run of the next-door neighbor’s home. Neighbor-invasion took many forms, but our primary activity was snooping around. In the den, windowless, plush-carpeted and stuffed with books and jazz LPs, we discovered an enormous magazine with a dark brown cover and a photo of the earth mostly in shadow. The title, in plump letters, read “The Last Whole Earth Catalog” and “access to tools.” At the bottom of the cover in smaller letters, “Evening. Thanks again.” More than half of the front cover is occupied by a photograph of Earth, with only a sliver illuminated, the rest, hidden in blackness.

A catalog? Or something utterly illicit, necessarily requiring stealth for future viewings? The catalog was too massive to easily open in a lap, so we had to open it on the floor and more or less lie on top of it in order to look through it.

Before the stupendous, shapeless mass of global corporate greed and manipulation—before Citizens United, before corporate-subsidized sports arenas and years (see “Year of the Depend Undergarment” and “Year of the Yushityu 2007 Mimetic-Resolution-Cartridge-View-Motherboard-Easy-To-Install-Upgrade For Infernatron/InterLace TP Systems For Home, Office Or Mobile” in an equally physically unwieldy book, Infinite Jest)—there was The Last Whole Earth Catalog, a glorious roadmap to DIY. Here one could find books on programming and pattern recognition, articles on how to raise sheep, shear, spin and weave, build domes, and stack sandbags for walls, and ride the rails (“when a train hits sixty miles an hour, the fool who attempts to sit is rewarded with a smashed ass.”). The lower corner of each right-hand page was sectioned off, reserved for the on-going narrative of Divine Right’s Trip, an addled hero journey by Gurney Norman.

Possibility—wild and limitlessness potential—was implied by the jam-packed content shown on these spreads. The pages were the same kind of yellow-oatmeal paper comic books were printed on. The entire catalog was printed in black ink and it wasn’t always easy to figure out what was being pictured, but evidently that didn’t matter because a detailed description accompanied each listing, along with an address of where to find whatever you might need. The Catalog was a revolution, it was cosmic, it was something that could give anyone access to real power, the power that resides in us all.

While “Power for the People” and “Counter-culture” weren’t part of my sisters’ and my consciousness at that moment (even though the print pattern on our bedroom curtains promoted “Keep on Truckin’” and “Save Water: Bathe With a Friend”), it was evident to us that this catalog was something magical. We somehow had an inkling that something was going on in these pages, something that might come in handy in the near future.

The Catalog didn’t sell anything, but instead offered information, resources and addresses, and reviews, suggestions and advice from other users. TLWEC shone a light on access to the technology, tools and ideas a person or group might want or need to live in a way that was of their own devising. Letters, questions, and practical advice and reviews from readers were published along-side the listings.

In my pocket-sized spiral notebook, I copied down addresses, concocting and planning my own return to nature. My scheme, a bit flawed and preliminary, was to build a treehouse for me and my future raccoon, down by the river. The Catalog had some excellent reference drawings that showed how I might outfit my bike in order to carry a substantial load, which to judge by my list of essentials, consisted mostly of books. Addresses for books on shelter construction, “The Impoverished Students’ Book of Cookery, Drinkery & Houseskeepery,” and “Wild Edible Plants” were jotted down. I thought “Cybernetic Seredipity” might be good for late night reading, even if not immediately realistic. As Fred Turner mentions in From Counterculture to Cyberculture, eighty percent of the items shown in the first The Whole Earth Catalog were books.

Nothing like a TLWEC would ever came into our own home. National Geographic was the only magazine our family subscribed to. I bought my first copy last fall, online, from a library in Nebraska. It’s a beautiful issue, the cover unmarred and a deep, thick brown, the body emits a faint odor of mildew and decaying newsprint. The spine was unbroken until I turned the catalog open on the table to read. A crack sounded from within the bulk and the two halves of the catalog slowly fell away. The spine separated, ripping a page that now straddled the gap.

On the back cover, there is another photograph of the earth, a swirly marble, and above the earth, there are these words, “We can’t put it together. It is together.”

______________

Boundless access via the internet, to tools and ideas, is of course obvious. Corporate tracking and interests are entirely more difficult to duck or even detect now, but the generous and exuberant spirit of The Whole Earth Catalog still thrives in software sharing communities like Open Source Processing, online libraries, free classes, and not to mention countless “how-to” videos on absolutely anything imaginable. Power FOR the People.

______________

A tremendous amount has been written about Stewart Brand, The Whole Earth Catalog and the Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link, aka the WELL. See the excellent book by Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture and the equally superb (and originally titled, “Power for the People”), Power to the People: The Graphic Design of the Radical Press and the Rise of the Counter-Culture, 1964–1974, edited by Geoff Kaplan.

see also: http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2011/AccesstoTools/

______________

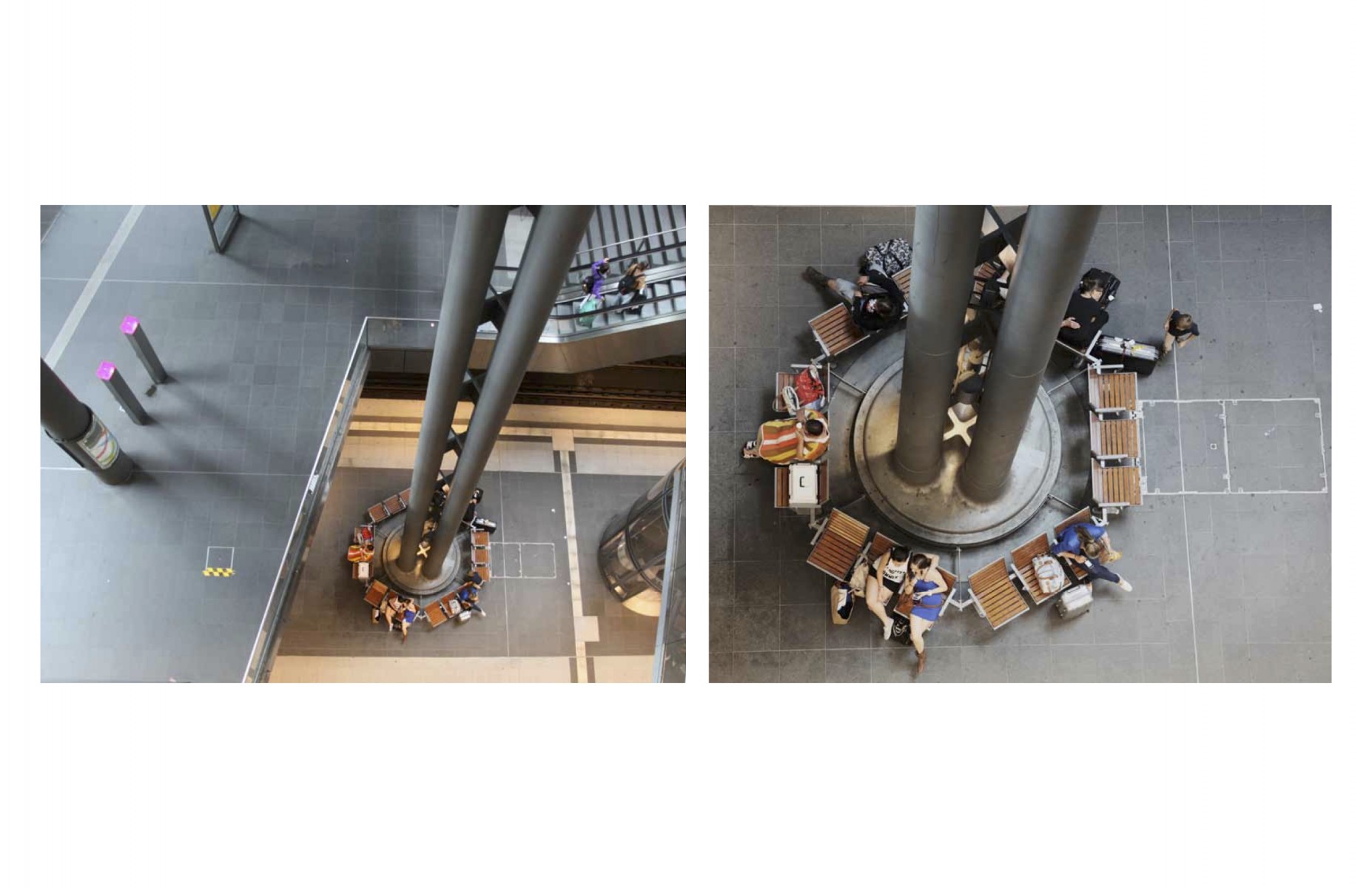

For this tenth year of DesignInquiry, the topic is ACCESS: who are we are trying to access and how do we open up access to the means and methods of design?