“It is as though the practices organizing a bustling city were characterized by their blindness. The networks of these moving, intersecting writings compose a manifold story that has neither author nor spectator, shaped out of fragments of trajectories and alterations of spaces.” (de Certeau, 1984)

“According to the systems view, the essential properties of an organism, or living system, are properties of the whole, which none of the parts have. They arise from the interactions and relationships among the parts.” (Capra, 1996)

////////////////////////////////////////////

Systems theory, as described by Fritjof Capra, posits that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Larger systems can be recognized by understanding the interconnected relationships that exist between discrete components in a network.

In “Designing the Immaterial,” Eric Benson of ReNourish suggests that graphic designers need to use their design skills in different ways—to redesign the systems by which we are bound. Benson writes, “The holistic nature of the design process is definitely needed to help design better systemic solutions for bigger issues like water rights, affordable and sustainable transportation systems, renewable energy production and dissemination etc.” (Benson, 2010) Benson is suggesting that, instead of a means to an end, designed objects need to be considered as parts in more comprehensive systems that affect broader social constituencies and stakeholders.

Systems thinking can be applied so long as the designer is able to recognize varying levels of complexity. When analyzing relationships between elements, it quickly becomes evident that seemingly independent systems exist within still larger systems, which intersect with other related systems of influence, and so on. For designers, there are a several ways to consciously design with systems in mind. With regards to environmental concerns, we can focus on detoxifying waste, air, water and energy use in the choices we make during the design and production processes. But we can also make a difference through the kind of design projects we choose to pursue.

Drawn to this idea, I travelled to Montréal in the spring of 2011 to participate in DesignInquiry: DesignCity. My chosen subject of inquiry focused on one of Benson’s suggestions—the graphic designer’s role in sustainable transportation systems, using Montréal as a case study location.

MULTI-MODAL SYSTEMS

Sustainable transportation solutions are often centred around reducing vehicle traffic on roadways. The transportation sector is one of the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions that accelerate climate change and therefore, vehicle reduction directly results in positive environmental consequences. Additional systemic benefits of this approach include reduced city expenditures for major roadway upkeep and repairs, while boosting access to local businesses by creating pedestrian friendly, compact communities. Citizens that use active transportation have an opportunity to adopt healthier lifestyles, putting less strain on the healthcare system.

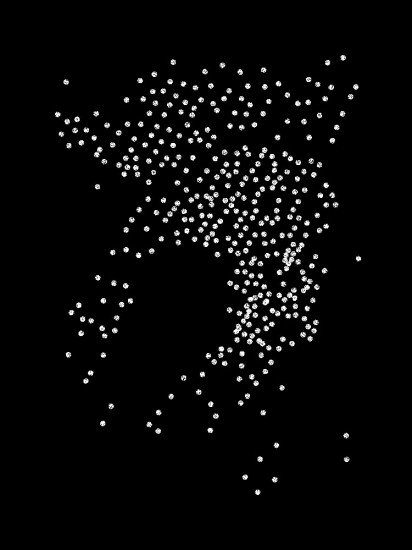

Montréal provides many alternative modes of transportation, including but not limited to, bus and Métro services (Society in Motion – STM), ride sharing (Allo-Stop), car sharing (Communauto), and the BIXI (“BIke taXI”—a rentable bike program). The City of Montréal supports multi-modal travel choices with a robust transportation demand management (TDM)* program that is planning future initiatives to increase use of public systems.

BIKE TAXI

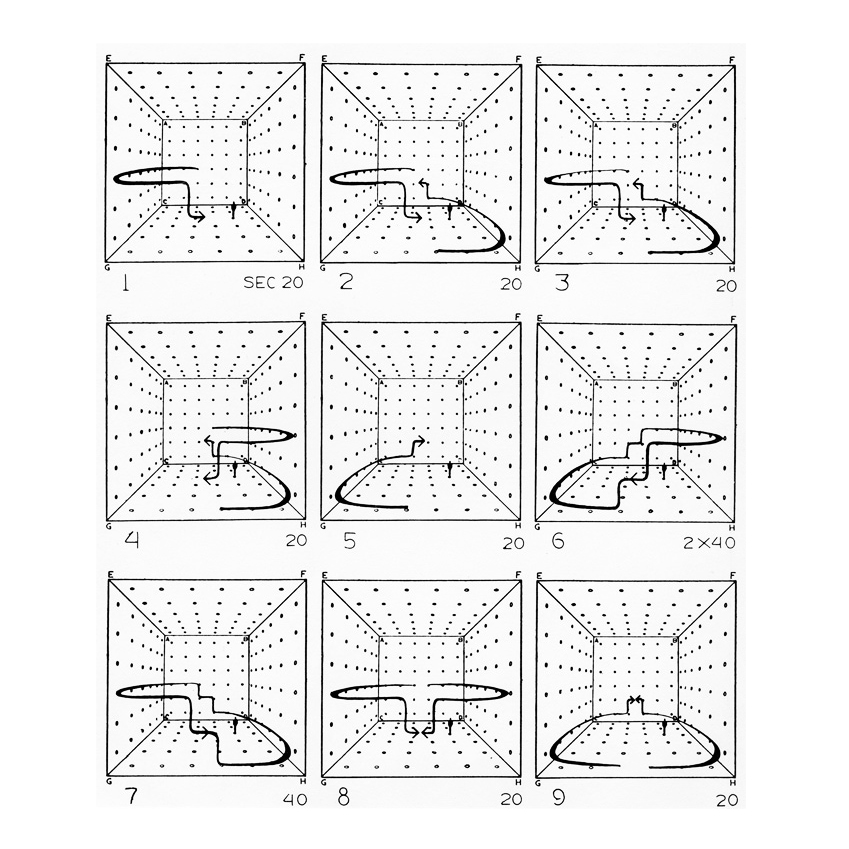

For this inquiry, I have focused on one mode of transit—the highly visible fleet of grey BIXI bikes zipping around the city. Cyclists can rent a bike from one of the hundreds of docking stations located throughout the city centre, draw an energetic line with their tires around the city, and return it to another station at their chosen destination. Users are then free to extend their line of travel with another mode of transportation, should they desire.

The BIXI bike system serves as an exemplary model of design passing through the threshold of producing goods (a great bike) to designing systems (a low carbon transportation option). It is also an example of reimagining what the future of transportation could look like.

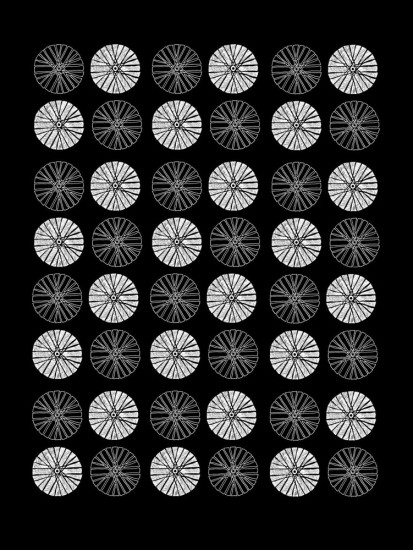

BIXI is a system designed by Montréal-based industrial designer, Michel Dallaire. The bike’s conceptual thematic is based on a boomerang, says Dallaire, “because it is the only object that comes back.” (Dallaire, 2011) The components of the BIXI system consist of: a modular, seasonal bike docking and locking system (pay station, bikes, tracking system), the city’s transportation planning and travel pattern research, and corporate sponsorship. BIXIs are partially sponsored by corporations, yet rely on public infrastructure, such as bike lanes and sidewalk storage space. Designing this system required a complex network of stakeholders ranging from robotics experts, industrial designers, policy-makers and business leaders working together to coordinate the production and implementation.

Since its introduction, the system has become an important component of the City of Montréal’s Transportation Plan and Sustainable Development Plan (2010-2015), which prioritizes the following actions: reduction of automobile dependency, calming of traffic in the city core, and assistance for Montréal businesses to adopt best practices for sustainable development.

This system gives Montréalers who like to cycle another option for getting around the city core from April to November. Yet, when asked about why his popular creation was successful, Dallaire simply says, “people are talking to each other more,” and, “it has augmented the friendliness of the city.” (Dallaire, ) Emerging from a system designed to resolve concrete environmental and infrastructure concerns, the BIXI has inspired unforeseen social interactions that contribute to an improved quality of life in the city.

SPATIAL STORIES

Dallaire’s response highlights the less tangible benefits of multi-modal travel. Whether planned or spontaneous, it is typically struck with unanticipated encounters that pull the private individual into public life. It is debatable whether all interactions are “friendly,” however, the psychological consequences of exploring the specificities of the city and unconsciously establishing personal migratory routes emerge through physical as well as human interaction. This describes an emerging culture initiated and nurtured by the BIXI bike.

Michel de Certeau suggested that ordinary practitioners of the city walk experience the city in a poetic way through pedestrian “speech acts.” (de Certeau, 1984). He suggests that individuals regulate changes in space through “Spatial Stories,” performing narratives through choices in paths, directions, and tactical practices. Pre-established geography becomes activated by spatial use and movement: “everyday stories tell us what one can do in it and out of it. They are treatments of space.”

To expand on de Certeau’s theories, multi-modal travel can facilitate a personalized narrative, traced by one’s navigation through the city—a trace that resolves shifting geography and pulls the pedestrian into cultural folds of the city, tucked between physical structures. This narrative begins to suggest a new understanding of how to treat the landscape by focusing on how people inhabit spaces, rather than imposing top-down systems for citizens to passively accept.

SPATIALISATION

In his essay, “Knowing Space/Spatilization,” Rob Shields describes different ways of knowing the city. He states that, “’knowing space’ is not enough—trigonometric formulae, engineering structures, shaping the land and dwelling on it. We need to know about ‘spacing’ and the spatializations that are accomplished through everyday activities, representations and rituals.” (Shields) Shields’ approach supports de Certeau’s distinction between top-down spatial imposition versus a personalized incorporation of the city through enacted behaviours. We “understand” our environments not through rational, scientific knowledge, but through our individual physical and experiential interactions over time.

During the Montréal inquiry, I scanned the BIXI system for graphic representations, identifying the company logo, the corporate branding, and city maps mounted in frames at every station—the “knowing” elements, according to Shields. However, the map frames were empty during the spring of 2011,opening up a space for tactical intervention. Taking advantage of this opportunity, I chose to mount my own hand-lettered signs that captured stories of first-time bike rides. These cycle stories were unremarkable and insignificant to most who might encounter them. They did not provide “useful” orientation within the city, information on how to rent a BIXI, nor did they advertise corporate sponsorship. However, the words were infinitely human, relatable, and reflective of a specific moment in time.

What resulted was a spatial practice and a story of space. Stories provide meaning to our everyday existence. The physical engagement of walking on sidewalks, pulling out a bike, peddling after friends, feeling the weather against your body and sharing intersection space, provide myriad narratives. In this author’s opinion, such chance encounters and embodied sensory experiences facilitate more potential for variety than a daily car commute.

My conclusion is that the communication designer’s role in a sustainable transportation system is to share the multi-modal story. Or, more precisely, to provide tools for the public to write their own narratives upon the city—in whatever forms these might take.

TACTICAL STRATEGIES

The strategic direction of a city develops as citizens discover and participate in the city plan with millions of spatial stories. A combination of walking, biking, and transit use activate the transportation plans envisioned by urban planning strategies and demonstrate the value of alternative modes of travel. It is hoped that civic planners will recognize this value, leading to further bike lanes and less emphasis on construction of parking facilities. Yet, these strategies are inconsequential if people don’t use them—placing the power in the hands (and feet) of the user. In this way,travelling around the city is designing the city.

Recognizing the geopolitical, health, and air quality implications of vehicle choices requires an acknowledgement of complex dynamics. A city is a large-scale system with unending variables (energy consumption, waste flows, housing, transportation, human behaviour, economic development, ecological constraints etc.). Simple choices about how we move our bodies through space represents a paradigm shift in the way we consume fossil fuels and generate wealth. The active pedestrian and rider is helping to combat unending growth and unsustainable development at the expense of ecosystem survival and personal health.

Understanding interrelated systems allows individual citizens to see how their actions affect realities such as climate change, clean water scarcity, and sustaining human life. To protect the climate and nourish all forms of life in the long run, we all need to become systems thinkers.

//////////////////////////////

*TDM is a set of policies and programs that reduce car use systematically. (Foord, 2009) As a result, the City of Montréal has a transportation plan that includes extending the subway system, creating dedicated bus lanes, implementing a “Pedestrian charter” and doubling bike lanes.

Cited References

Benson, E. “Designing the Immaterial.” DesignInquiry Journal. Retrieved from https://archive.designinquiry.net/journal/uncategorized/1331/designing-the-immaterial/. 25 March 25, 2011.

Capra, Fritjof.

Dallaire, Michel.

de Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Foord, C. Transportation Demand Management. Vancouver: Fraser Basin Council, 2009

Haraldsson, H. V. Introduction to System Thinking and Causal Loop Diagrams. Lund: Lund University Press, 2004.

Kingwell, Mark. “The City as a Work of Art.” My City is Still Breathing Symposium. Retrieved from http://www.artsforall.ca/index.php/AFA/article/my_citys_still_breathing_a_symposium_exploring_the_arts_artists_and_the_cit/. 1 May, 2011.

Lefebvre, H. La Production de l’espace (2nd ed.). Paris: Anthropos, 1981.

Rob Shields. “Knowing space/Spatilization”