I have an archive in my basement of my children’s writing. Anything they ever wrote on—post-its, cardboard—with whatever, on whatever, I’ve kept it all. By digging through these artifacts with the intention of organizing them into simple chronology, I wondered if the 21st century child’s experience of learning to write just might parallel the history of the development of writing. I noticed in the stacks that they used pictography, logography, and personal symbol systems. This trajectory is of course supported by the development of the hand and cognitive skills as they enter into the artificial visual vocabulary and the cultural allegiance to sound symbols they are taught.

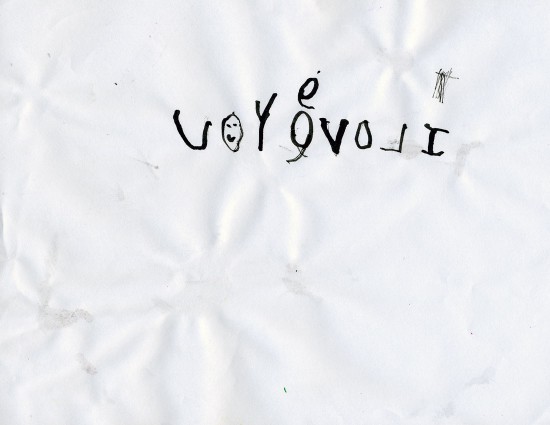

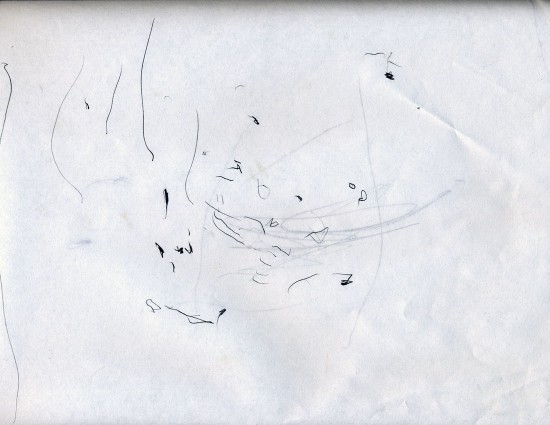

Children begin speaking around 1 year old, testing the communication tools of the voice, lungs, mouth, and gesture. Communication lives solely in the body at this age. The senses are fully loaded with intake and expression, ‘language’ is emotional, gestural, and intuitive. They also begin to practice the language of marks—combining motor skills with tools and surfaces. This proto-writing has weak connections to oral language but a consistency in respect to arrangement and isolated lines.

The words ‘drawing’ and ‘writing’ are used by a verbal toddler to describe these marks. They’re working at developing a visual idea which they imply through spacial considerations—figure, ground, and an understanding that making a single mark creates an inside and an outside, thereby setting the stage for an understanding of deep visual communication strategies.

From the perspective of linguists and historians as well as the child, proto-writing is not a deficient representation of language, but a successful means of representing knowledge. This writing with weak connection to oral language attempts to transmit information from one individual to another, and for the child is successful and useful for the level and context of communication at hand.

Proto-writing introduces the possibility that a variety of techniques are available for coding information in effort to express experience or thought.

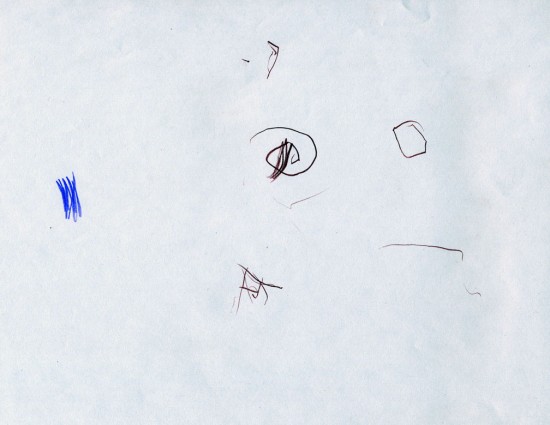

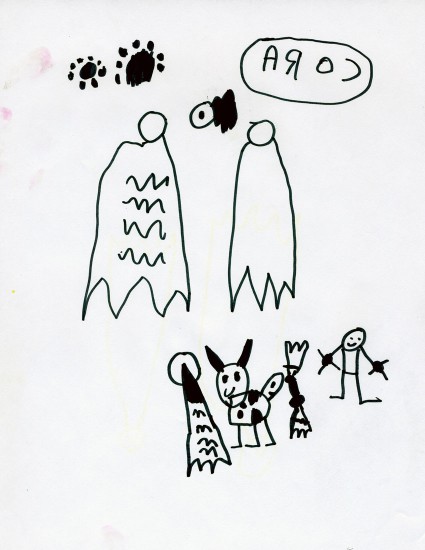

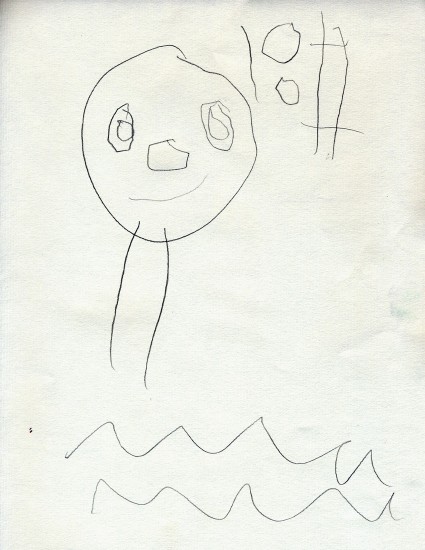

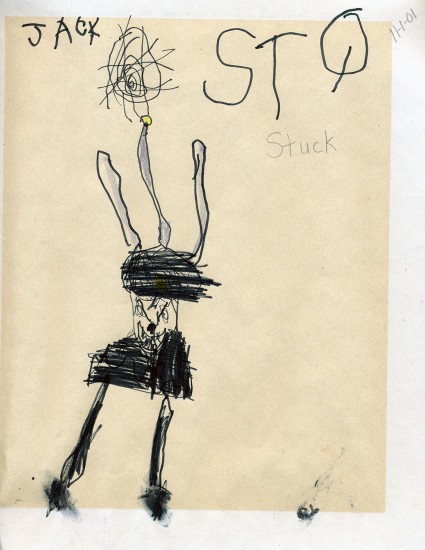

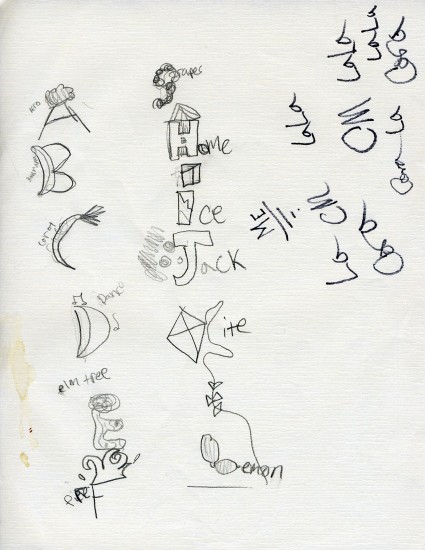

Pictography, or picture-writing is a form of proto-writing. Not attempting to record the sounds of words, the context of mark to mark is how the story is told by the pre-schooler. Within each context or page, a system approaches and may be easily repeated. The child-communicator defines space with enclosure, plays with scale, and controls distances between elements.

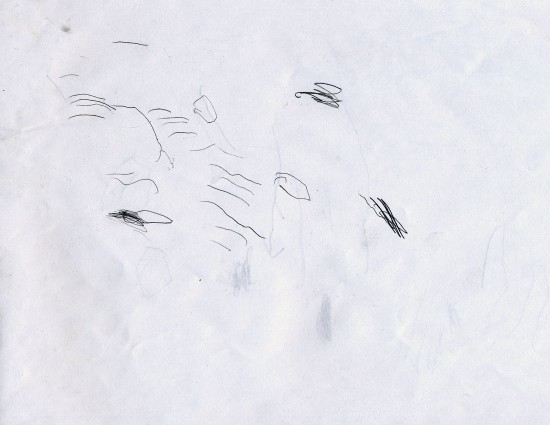

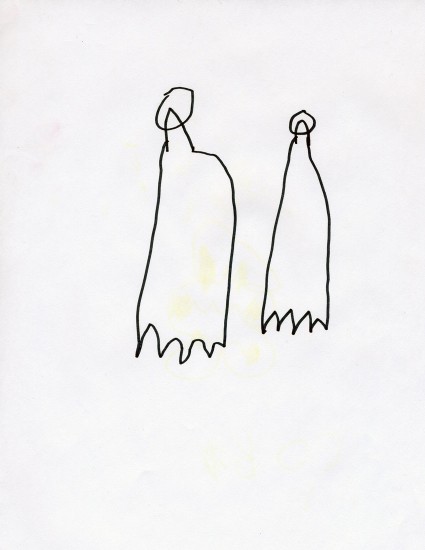

These pre-writing systems begin with images used as words, literally depicting something. But pictograms of this kind are limited—some physical objects are difficult to depict, and many words are concepts rather than objects. The edge between verbal, visual, and tactile expression expands as the child is encouraged to use the visual as another entrance into her everyday culture. ABOVE: ‘Me and you’

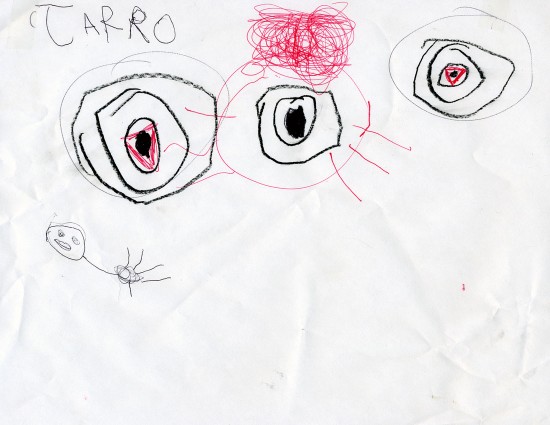

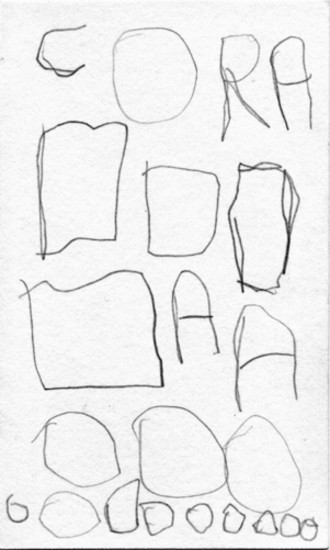

In word-writing, or logography, the object depicted is to be spoken aloud. ‘Characters’ hold both sound and idea and must be learned because they are specific to the author. ABOVE: ‘Open eyes watching’

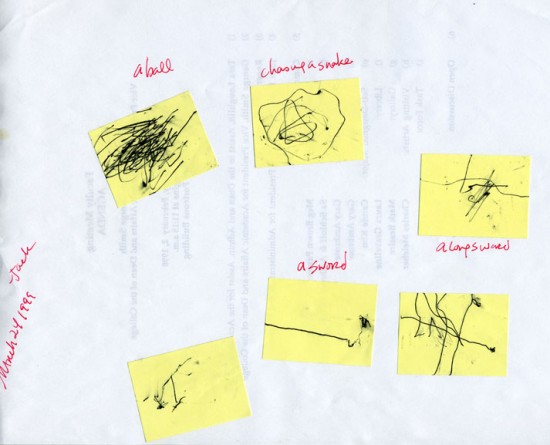

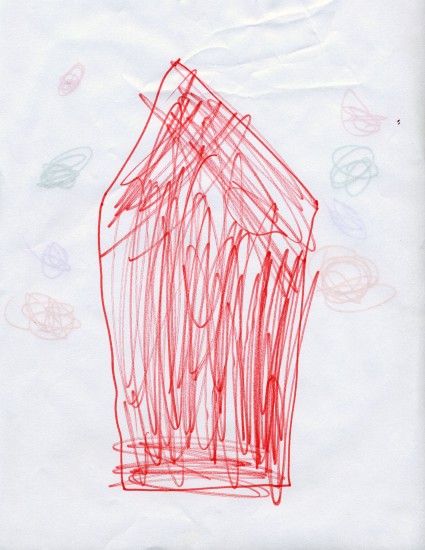

Entering the world of symbols, children test combining pictures with concepts, testing the marriage of marks and mnemonics in abstraction. Symbols date to written language development before 4BC and come naturally as well to the 21st century child’s vocabulary of images—simple geometric forms with storytelling possibilities. ABOVE: ‘Family table’

Over time, individual pictograms become repeated, standardized, and perhaps abstracted. Complexity is added by context, sequence, and symbol relationships. Children naturally understand that a symbol is bound to a system-external referent and meaning is related to the object the symbol represents.

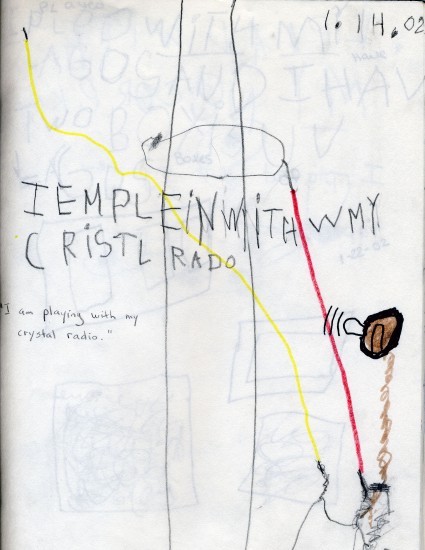

Symbols and mixed systems are joined with sound and speech to ultimately represent spoken communication, a type of rudimentary ‘reading’. ABOVE: ‘House’

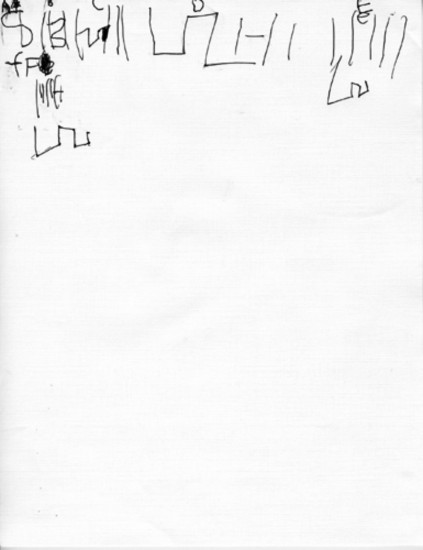

ABOVE: ‘House that you have to guess which light switch turns on the light in the studio—you can only go up the stairs one time.’

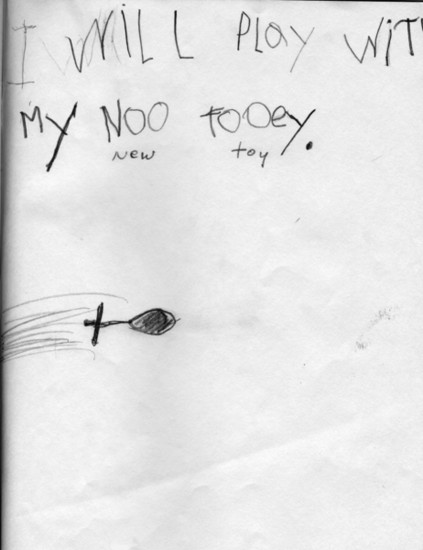

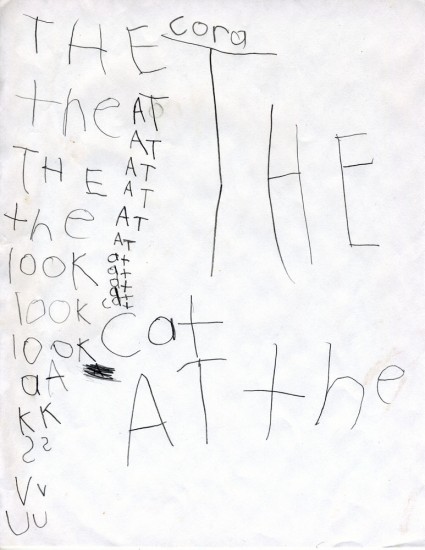

Imitation encourages pre-writing, where symbols represent linguistic elements of sound. Children pretend to write their name over and over—mock letters become more conventional and real letters start to emerge. Now horizontal strings of letters are formed with an awareness that arrangement is necessary to make words, just like specific sounds need to be sequenced for understanding spoken language. ABOVE: ‘Cora’

Symbols are combined with signs of attempted writing, such as a signature repeatedly appearing in a certain position. ABOVE: Cora’s drawing of ‘Cora’, her signature above and her written ‘story’ at the bottom

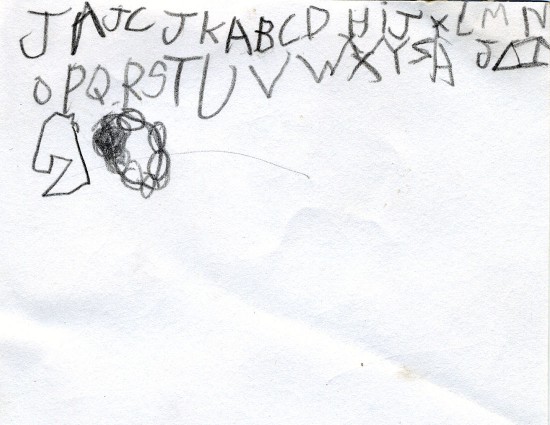

When phonetic sound assumes priority in the writing system, incomplete (pre)writing becomes complete writing. Now the child tests the system by clustering, inverting, mirroring, and imitating scripts that replicate the writing of their culture.

In English, consonants (like Phoenician writing) are taught to be written first, then vowels (like the Greek addition) are added. Words are used as captions for images, emphasizing for the child that the story belongs in the words, in sound-symbols.

Writing was born out of the need to record the events of everyday life—throughout history, as well as for one child—we tell stories with standardized and systematized symbols and signs that we’ve connected to the sounds of language.

While Jack and Cora, now ten and twelve, have not entered into one writing system that is superior over any other used in the world today, they are now fluent in a graphic symbol system that developed in similar ways as their own skills and steps—from proto-writing to complete writing. Now they can communicate stories, feelings, and ideas to someone else, to themselves, over distances, and for later. Nuance, voice, form, and richness of the written word comes next.

Narrative is the proof of existence, writing is a social process. The successful process of standardization of complete writing systems means that humans can interact outside of conversation, body, and time.

WIth images and sound-symbols the child becomes the poet, the artist, writing down expression out of desire and necessity.