DesignCity: Montréal raised many questions about both cities and design by investigating Montréal as one of the intense assemblages that we call cities–particularly in its self-conscious UNESCO designation as a “City of Design.” Where the concepts of both “design” and “cities” might seem to be specifically human practices, I would like to propose that there is a more interesting and responsive way in which to understand both the concepts and practices of design and cities. This proposed approach to design processes and the construction and negotiation of cities is much more appropriate to where we find ourselves currently–that is, this long moment when most of us (at least those of us not stuck in some mulish ideological stance leaning right-perverse) acknowledge that climate change is an aggravated response to cumulative and un-thoughtful human behaviours.

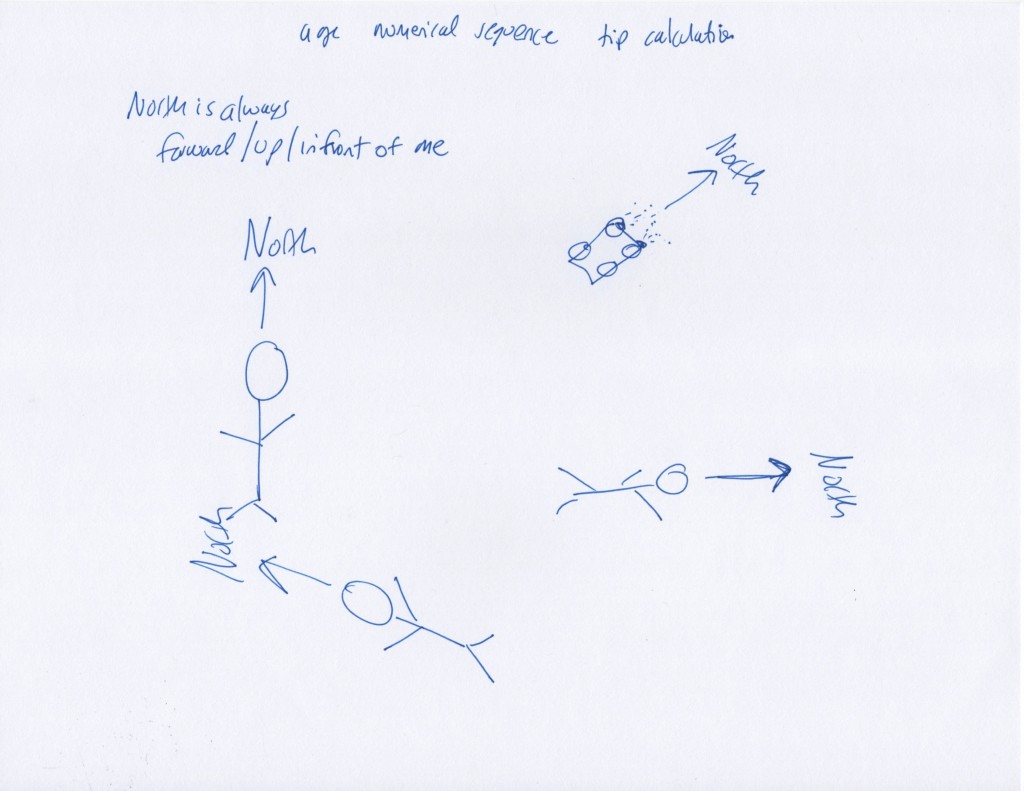

The contemporary sense of the word “design” emerges from the actions of designation–to somehow sign or mark off one element or territory from among other assemblies. There is an implicit and initially un-signed context, constituting a place and time that precedes designation. Thus, design practices invent through creative but selective iteration. They articulate (or re-articulate) something that may vaguely exist, but may not have been previously formulated in a particular and intentional way.

However, where designers bring creative intent to their practices, there is also an important quotient of responsive and serendipitous improvisation to their actions. This is the necessary engagement and entanglement with the time, space and material–the rich and messy context–in and with which we design. As designers, we point towards or draw attention to something that is already present. But, to design is to inventively and creatively decipher or reiterate that preexisting something with new and different emphasis. Robust invention does not emerge from rare air (the proverbial vacuum), but instead draws from thick matter, rich and chaotic with the possibilities of both incoherence and new articulations. Design is reiteration and renewal. It is a daily practice that points towards what we wish to celebrate, sing and shout about, in the where and when we find ourselves–quite possibly in an urban context. And as designers collaborating with more than human contexts, what is it that we each choose to point towards, to mark off and designate as particularly noteworthy and inspirational? What might our responsibilities be in this regard?

Where most cities are in some sense designed, relatively few seek to overtly and self-consciously declare themselves a “City of Design.” Certainly, the UNESCO designation brings a prestigious recognition to any city. However, first and foremost, this designation must be actively sought. A municipal body must prove that their city fulfills the designated (indeed designed) criteria: the eager city-candidate must show that it fosters and furthers cultures of design, both through formalized institutions (schools, museums and societies) as well as through a critical mass of a lively and varied design practices.

Cities are made, practiced, negotiated and lived by a collective that is far from always harmonious. Thus, cities are always tense collaborations between many–and certainly, not just humans. The intense assemblages of urban settlements are negotiated and respond to the enabling environment, the more than human forces, and the idiosyncrasies of dynamic place.

Montréal is a city on an island in a river archipelago in a valley; it is joined to adjacent islands and other shores by bridges in seemingly constant need of repair. Both the island and the city are currently named for the large hills of igneous rock at its southeastern belly that have stubbornly resisted the erosion by glaciers, water and wind over many centuries. It is only since the 1500s that this hill has been called regal–Mount Royal, or, in colonial era French, Mont Réal. But before this, the island was named Tiohtiake–the parting (or meeting) of peoples and waters in Kanienkehaka (Mohawk)–for its strategic location as both portage and meeting place at the confluence of two major rivers (the St. Lawrence and the Ottawa Rivers). These different names are selective designations–the beginning, perhaps, of the city’s design. Each naming emphasizes different aspects of place, distinct value systems and varying perceptions of human relations with the larger surrounds.

This place and its human settlements have likely had many other names in other human languages that have been sadly lost to us through the passage of time and the ruptures of displacement, death and forgetting. As much as Montréal is a collective expression of human intent to thrive and prosper, the city is equally a material response to this unique configuration of rivers and rock, soils and rich overlapping ecosystems of fauna and flora particular to this part of the St. Lawrence Valley. Moreover, the city may even be understood as a collaboration between the human and the more than human in a tangled story of trial and error, accident and intent – an always emerging story that is best understood from a multitude of perspectives and is certainly far from over.

This is a very brief argument that, if we are to be self-conscious and thoughtful about cities and design, perhaps we may best approach these practices with an intelligence humbly open and eager to engage phenomena that cannot yet easily be understood or even articulated (human and more than human inclusively); with a willingness to collaborate with the material accidents and serendipity of particular places and events; and with a recognition that we may indeed choose how we respond and are responsible to all that comes before and inspires design of places and events, large and small.