PREFACE

This is a guide to built joy—joy encountered in and experienced through the built environment. This type of joy is a rare thing, an architectural endangered species that we encounter all too infrequently in our daily lives. But, like tracking the Northern Spotted Owl or hunting the Black Perigord Truffle, pursuing built joy is worth the effort. Whether you are a casual environmental psychologist, a contemporary situationist, an architectural enthusiast, or an old-fashioned joy lover, this guide will help you find the elusive emotion across all constructed domains and habitats, be they urban, suburban, or rural, local or global. Equally useful in the home and in the field, this guide provides a starting point for exploring diverse types of joy in the built world.

INTRODUCTION

This guide uses the term built joy to describe occurrences of exultation and pleasure in the built environment. This guide uses the term “built environment” to describe those landscapes deliberately and intentionally constructed by humans for human use and occupation. Once the fundamental need for shelter was satisfied, it seems likely that some among the earliest builders endowed the spaces they made with joy. It also seems likely that some among the earliest occupants felt joy in those spaces. By the Roman era, the existence of built joy was a certainty, evident in the famous triad of virtues that Vitruvius articulated in De Architectura (written about 25 BCE). After firmitas and utilitas—dealing with pragmatics of durability and function—Vitruvius argued that all good building required venustas. Though it is generally translated as beauty, venustas is understood to surpass mere aesthetics, moving towards a thing fully felt by both designer and occupant. In the 17th century the British theorist Henry Wotton identified this as delight. In the 20th century the American architect Louis Kahn identified it as joy.

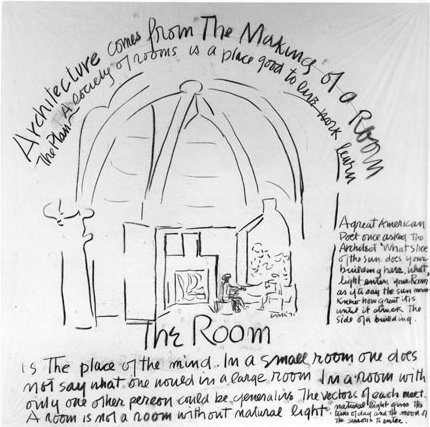

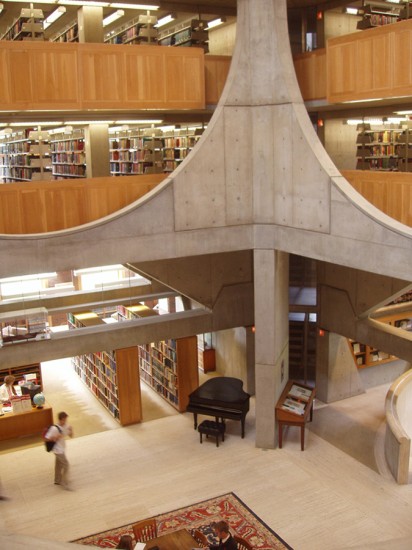

While most architects and theorists argued that the joyful intention of a space’s designer was a prerequisite for the joyful experience of a space’s occupant, Kahn believed that joy had its own a priori existence. For Kahn, joy was an “impelling force that was there before we were there” and “this force of joy” was constantly “reaching out to express.” It was the work of the designer to seize this joy and give it form. It was the work of the occupant to be receptive to this joy and to feel its power. But no matter how much Kahn was committed to the primacy of the architect as creator, in his formulation the occupant was not reduced to mere passivity. In experiencing built space the occupant was an active participant in uncovering “that which joy is made of.” [1]

Louis I. Kahn, The Making of a Room, 1971 & Philips Exeter Library, Exeter, New Hampshire, 1971, interior

This guide is premised upon the agency Kahn recognized in each of us: every encounter we have with the built environment is a potential experience of joy. Finding that joy is not always easy—Kahn calculated that only 5-10% of those who make buildings could be counted on to make joy an architectural priority. The rest are preoccupied with responsibilities to safety and welfare, and focused almost entirely on problem solving and value engineering of program, structure, etc. As a result, too many of our buildings exclude concerns that are the domain of joy, and deliberately refuse to engage emotion, pleasure, and the sensual realm.

Lest joy seekers become disheartened at the outset, it is important to note that even buildings lacking intentional joy are not devoid of discoverable joy. As physical objects, they could hardly be otherwise: a building’s manipulation of materials and space, orchestration of light and movement, and transformation with age and weather are all opportunities for joy. When the physical intersects with the social, the potential for built joy multiplies almost infinitely. Thus, no matter how much building culture regards joy with suspicion, “really, joy will prevail.” Users of this guide are encouraged to keep this—the conclusion of Kahn’s 1973 lecture—well in mind as they venture into the field in search of built joy.

HISTORY

In the long history of architecture, joy hovers just below the surface, waiting to be probed and exposed, identified and deciphered, as in archeological excavation. The historic episodes that follow reveal this joy by exploring key concepts that have informed joy’s built manifestations through the ages, all of which remain relevant in the contemporary landscape of the 21st century.

Gothic Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, 1163 – 1345

Monumental

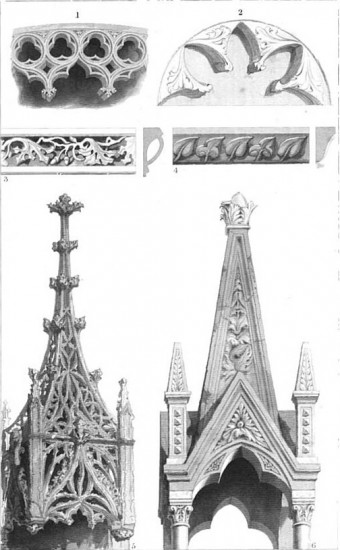

Though built joy has undoubtedly existed for as long as there have been buildings, the most frequent historical manifestation for which we have evidence is in monumental structures. Writers across the Empire expressed their delight with the rich appointments and expansive spaces of Roman baths. The devout, from theologians to pilgrims, described the ecstasy they felt when confronting the stained glass and soaring heights of Gothic cathedrals. These were aspirational buildings, intended and experienced joyfully. These were also propagandistic buildings. But however oppressive the institutions capable of producing monumental buildings, their monuments can still produce joy. Indeed, despite centuries of religious wars and abuses, the buildings of the sacred realm have been the most consistently joyful. Perhaps this is because in sacred buildings, unlike in most other types, transcendence is very nearly a functional requirement. Across the great religions, sacred buildings are designed as sites of contemplation and demarcation, separating the everyday and spiritual worlds. While this is no guarantee of joy, it is a useful precondition, deliberately setting the stage for a vivid emotional experience.

“Primitive Hut” frontispiece from Laugier’s Essai sur l’Architecture, 1755

Quotidian

Though the specialness of sacred space contributes to its joy potential, quotidian or everyday spaces can also produce joy. This is a fairly recent phenomenon, dating only to the 18th century in Rousseau’s romanticizing of the homme sauvage in On the Origin and Foundation of the Inequality of Mankind, and the subsequent canonization of the primitive hut as an architectural equivalent in such treatises as Marc-Antoine Laugier’s Essai. While those Enlightenment theorists were primarily searching for figures (human or built) uncorrupted by civilization, they inadvertently provided a foundation for finding satisfaction in roughness and simplicity. A century later, this idea reached its maturity in the thinking of John Ruskin and William Morris and their celebrations of pre-industrial craftsmanship, from The Stones of Venice to the Red House at Bexleyheath. When Ruskin declared in 1857 that “joy, humility, and usefulness always go together,” he could have been describing the ideology of Arts & Crafts designers and the desires of Arts & Crafts consumers—then and now—who learned to take pleasure in the bungalow and the cottage rather than the manor and the villa. [2]

John Ruskin, “Surface and Surface Gothic,” plate XII from Stones of Venice, 1853

William Morris and Phillip Webb, Red House, Bexleyheath, 1859, garden façade

Valorizing the joy of humble authenticity continued into the 20th century when modernists like Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier added the industrial vernacular to a growing list of everyday built joy. In their embodiment of the zeitgeist of the Machine Age and especially in their elegant, but utilitarian resolution of form and function, the grain elevator, the daylight factory, and the airship hangar produced sighs of pleasure after the aesthetic excesses of the fin-de-siècle. And the modernists intended their own buildings, derived from those industrial forms, to have the same effect. Contemporary joy seekers can approximate that early modernist thrill by locating buildings made from our post-industrial equivalent—shipping containers.

Shigeru Ban, Nomadic Museum, New York City, 2005

Pop

From here, with Reyner Banham, Tom Wolfe, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown as tour guides, it was a short step to finding joy in the exuberant everyday landscapes of Main Street and the Strip. The zeitgeist of late capitalism in the 1960s and after may have produced less lovely forms but it was possible to revel once again in aesthetic excesses, now of the kandy-kolored-neon variety.

Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” offers an important theoretical foundation as it attempts to explain “the sensibility of an era” that made an appreciation of Las Vegas possible. The Notes are suffused with manifestations of joy and what it means to be in a joyous state. From Note 54: “The man who insists on high and serious pleasures is depriving himself of pleasure; he continually restricts what he can enjoy.” From Note 55: “Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation—not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy.” From Note 56: “Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as ‘a camp,’ they’re enjoying it.” [3] Though “camp” was a far more complex and transgressive practice than Sontag presented in her essay, in upending cultural hierarchies and collapsing dichotomies of taste, it broadened the possibilities of joy, built and otherwise.

Louis Sullivan, Wainwright Building, St. Louis, 1894, detail of piers and spandrels

That Dare not Speak its Name

It is worth observing, however, that while joy is everywhere apparent in “Notes on Camp,” nowhere does the word itself actually appear in the text, unless accompanied by the prefix “en-.” This is not mere semantics: joy’s implicit sincerity meant that it could not be expressed explicitly in an essay dedicated to toppling high seriousness. This omission has a direct parallel in architectural discourse in the mid-20th century and by extension in manifestations of built joy into the 21st.

In his 1924 Autobiography of an Idea, Louis Sullivan wrote about joy unabashedly and unselfconsciously. “The Free Spirit is the spirit of Joy. It delights to create in beauty. It is unafraid, it knows not fear.” [4] This is the same effusive spirit that animated his buildings; what are the entry, cornice, and spandrels of the Wainwright in St. Louis if not joy rendered in molded terra cotta? That building dates to 1894 and it’s a 19th century sensibility that underlies Sullivan’s autobiography, despite its Jazz Age publication date. Sullivan could be open about joy because his romantic inclinations tended backward not forward.

By the time Sullivan’s fictional alter ego made an appearance in Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel The Fountainhead, his pronouncements were meant to seem hopelessly old-fashioned and out of step with the times: architecture is “a consecration to a joy that justifies the existence of the earth.” Of course, that ideal of joy is precisely what make the buildings designed by Howard Roarke, the novel’s misunderstood architect hero so distinct, and despised: “Your buildings have one sense above all—a sense of joy. Not a placid joy. A difficult, demanding kind of joy. The kind that makes one feel as if it were an achievement to experience it. One looks and thinks: I’m a better person if I can feel that.” [5] It hardly needs mentioning that in the thinly veneered fictional America of Rand’s novel, that kind of joy was the rarest of species of all.

Just as The Fountainhead was hitting the bestseller lists, the architect Morris Lapidus was beginning to make a name for himself with buildings that embodied a very different kind of joy, one meant to be accessible and effortless in its evocation of “emotion in architecture.” In dozens of stores and especially in hotels, such as the Fontainebleau in Miami Beach and the Summit in New York, Lapidus produced the kind of shameless, dazzling commercial modernism that critics despised and clients and customers loved, all sweeps and curves and cantilevers overlaid with with riotous decoration. “They call my hotels corn but they’re better than corn. They make people happy, excited, titillated.” By 1970, the pop sensibility allowed those feelings to be freely expressed and, with equal parts irony and playfulness, Lapidus’s work was dubbed “the architecture of joy.” [6] Built joy had not quite come full circle, but it had come close. If the past four decades have not occasioned more instances of explicit joy this is because architecture takes itself far too seriously to be serious about joy. Which is why this guide is necessary.

CONCLUSION

From the ruins of Rome to the ruins of Detroit, from the cathedrals of Europe to the Mall of America, today we are free to seek built joy everywhere, guided not by ideals of beauty or theoretical discourse or historical precedent, but by our personal sympathies and social circumstances. Of course those sympathies, however individualistic they may be, are invariably shaped by ideals, theories, and history. And those social circumstances, whether cosmopolitan or provincial, are always relative. Joy in the built environment is continually in flux as it moves from intention to reception and from form to content. All the joy that has come before will influence all the joy we have yet to discover.

________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Louis I. Kahn, “1973: Brooklyn, New York,” Perspecta 19 (1982), 89-90. This was one of Kahn’s last public lectures, delivered the year before he died.

[2] John Ruskin, “A Joy Forever (1857)” in The Works of John Ruskin vol. XVI (1880; rpt. London: George Allen, 1905), 155.

[3] Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp,” (1964), rpt. in Sontag, Against Interpretation (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1966), 291-292.

[4] Louis Sullivan, Autobiography of an Idea (1924; rpt. New York, 1956), 258.

[5] Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead (1943; rpt. New York: Signet Books, 1996), 80, 518.

[6] Morris Lapidus, “A Quest for Emotion in Architecture,” AIA Journal 36 (Nov. 1961), 56, 67. “Crazy Hat, Bright Tie,” Time (9 May 1960), http://www.time.com/time/archive/, 49. See also Gabrielle Esperdy, “I am a Modernist: Morris Lapidus and his Critics,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 66 (Dec. 2007), 494–517.