“…all semiotic space may be regarded as a unified mechanism (if not organism). In this case, primacy does not lie in one or another sign, but in the ‘greater system’, namely the semiosphere. The semiosphere is that same semiotic space, outside of which semiosis itself cannot exist.” (Lotman, 2005)

The Metropolis immerses its occupants in a dense visual (and graphic) environment, an organic ecology of visual code, an urban visual language, a graphic landscape. It is highly mediated and deeply annotated. Cultural conventions and mythologies and … create our perception of the city. Typographic typologies comprise a graphic ecology as do the conventions of advertisements, signage and wayfinding, and every other form of graphic visual.

Yuri Lotman’s theory of the semiotic continuum, the semiosphere, models itself on the biosphere. It is a contained, self-regulating ecological system of and by language. Like the biosphere, the semiosphere can be seen both as a whole and as an interconnected, interdependent, systemic complex; a semiotic organism of nested semiotic organisms.

In Lotman’s theory, the primary task of culture “is in structurally organizing the world around man (Lotman, 1978)…” Within the semiosphere, language functions as a “diecasting mechanism” creating an “intuitive sense of structuredness that with its transformation of the “open” world of realia into a “closed” world of names, forces people to treat as structures those phenomena whose structuredness, at best, is not apparent.”(Lotman, 1978)

We might imagine that in the highly mediated landscape of contemporary culture, graphic/visual language (a complex of typologies and forms evolved from the larger and more general sphere of language and a subset within the semiosphere) plays a significant role as a “diecasting mechanism of culture structuring reality into textual/visual “names”.[1] We design reality which defines us. Or as Tony Fry states “Humans design, but are, in turn, designed by what results from this designing — be it as things, symbolic forms or traditions.” (Fry, 2003)

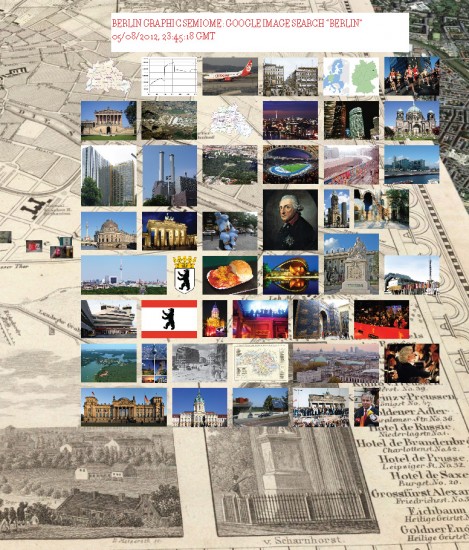

05/08/2012, 23:45:18 GMT’, Ad Hoc Atlas Berlin, 2013.

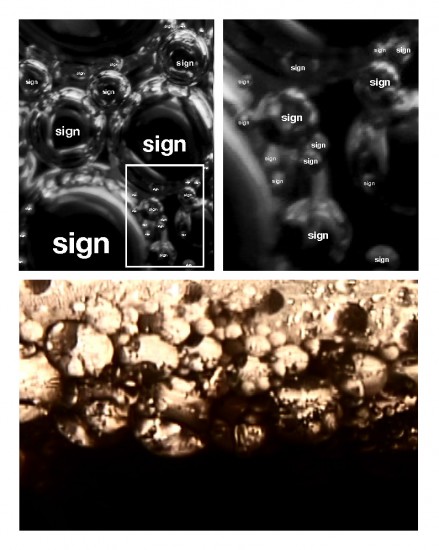

The city is comprised (partly) by a graphic and semiotic landscape that covers the urban field, the geographic surface. It does not adorn, but rather builds (or as the German “bild” which is to picture) creating structure of the social sphere. The complex and interconnected and interdependent structure that the graphic semiosphere creates is pervasive but not readily apparent. It is a complex of interconnected subsets (like biomes within the biosphere) within the cultural ecology of the semiosphere (a semiome?). It is how we picture (and so build) the city.

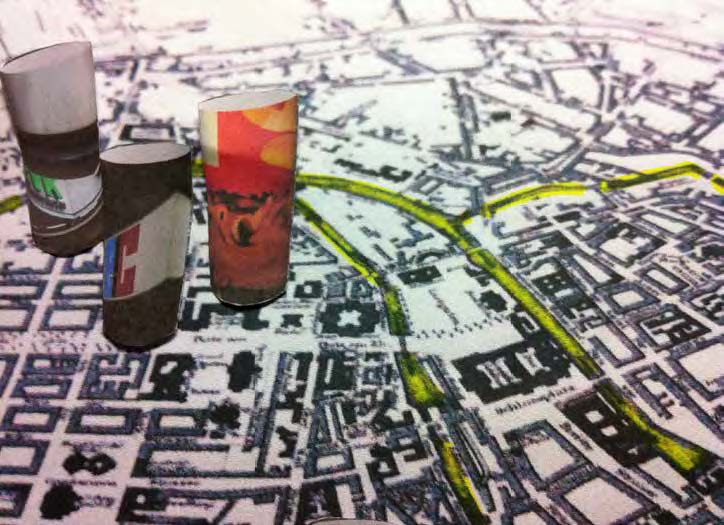

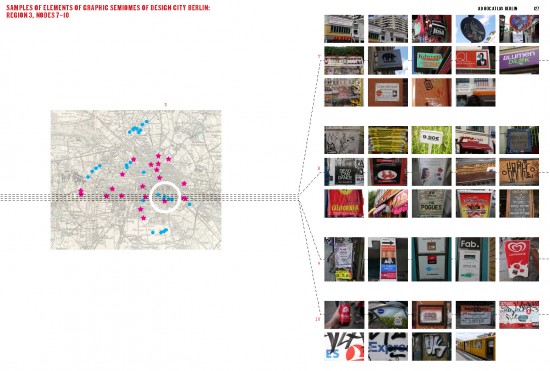

The design artifacts of the Ad Hoc Atlas Berlin, some of which are presented here, are records and investigations of wanderings in and observations of the graphic semiosphere(s) of Berlin.

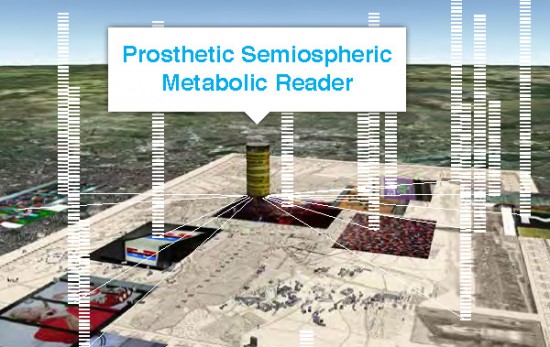

The graphic semiosphere is mapped. Specifically the infinitesimal semiomes of Berlin as a City of Design. The geographic location and boundaries (called nodes) of the semiomes are determined by two rationales 1) from a survey of design professionals, and 2) from the excursions performed by the Design Cities group. Locations are compared on a map of Berlin (with transit and waterways in the hope that these might show some patterns or tendencies.) Image data of small and discrete elements of the graphic semiosphere were collected as geolocated photographs and organized by region. It is important to note that a complete set of the elements of the graphic semiosphere is impossible to create due to scale (incalculable) and the constant shifting nature of the sphere. A prototype for a Semiospheric Metabolic reader was proposed and presented here as a way for the city to observe it’s own semantic psyche. It is both reader and transmitter. It scans the vast landscape of the graphic semiosphere recording the discrete elements while also projecting these across the city as an inflective upon the semiosphere in a semantic causal loop.

[1] Clearly other forms of aesthetic production are at work here. Film, television, literature, art, the multi-variant forms of the internet all have significant roles. All of these forms, and others, constitute subsets of the semiosphere. Here, I am limiting my argument to graphic design. This would include all graphic forms and would cross over various media.

Fry, Tony. “Designing Betwixt Design’s Others.” Design Philosophy Papers 2003/04, no. 6 (2003).

Lotman, Yuri. “On the Semiosphere.” Translated by William Clark. Sign Systems Studies 33, no. 1 (2005): 208

Lotman, Yu. M., B. A. Uspensky, and George Mihaychuk. “On the Semiotic Mechanism of Culture.” New Literary History 9, no. 2 (January 1, 1978): 213