FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND, Peter Hall (2006)

Don’t go to conferences! It’s mini-vacations, boondoggling. No more conferences!

— Camille Paglia, Sex, Art, & American Culture

Despite the massive growth in the numbers of designers in recent years, conferences catering for this burgeoning profession are often lacking in consistency and rigor. Common complaints heard about professional design conferences are that they follow a show-and-tell format of celebrity designers wheeling out well-rehearsed presentations of their work, or simply focus on the delivery of tips and tricks of business development and software operation. The large size of conferences often precludes meaningful participation beyond applause and question and- answer sessions. Conference themes are often vague, and the level of discourse often fails to get beyond a general agreement that design is useful/powerful/important. In contrast to related disciplines such as architecture and art history or the relatively new arenas of digital arts, design conferences seem to struggle to get beyond a communally expressed desire for validation. At the same time, professional gatherings are important opportunities for knowledge- sharing, networking, and collaborative learning—activities too important to neglect.

DesignInquiry was established as a response to a perceived gap between academic and profession-based learning; between the richness of participatory learning at design school and the frequent lack of time for experimentation and research in the working environment. In its first years, 2004 and 2005, the event attracted an extraordinary showing of key figures in graduate-level design education, with heads from programs at schools including California Institute for the Arts, Cranbrook Academy, Rhode Island School of Design, Yale School of Art and Art Institute of Boston. Approximately 50 participants attended each year.

Still based at Maine College of Art, the event was organized around a central topical issue with several concurrent faculty-led workshops supported by frequent “walkabout” inter-room critiques and morning lecture presentations by faculty. These first two years yielded some lessons: The open structure and concentration of high-profile educators initially bred rather lengthy discussions of professional and educational issues in the early days of the event, but this was subsequently subsumed by a frenetic atmosphere of making. This progression from critique to production was in many ways a literal realization of graphic design’s shift in the academy through the early part of the decade from critical theory to the idea that the act of designing can be a form of criticism (also termed critical practice).

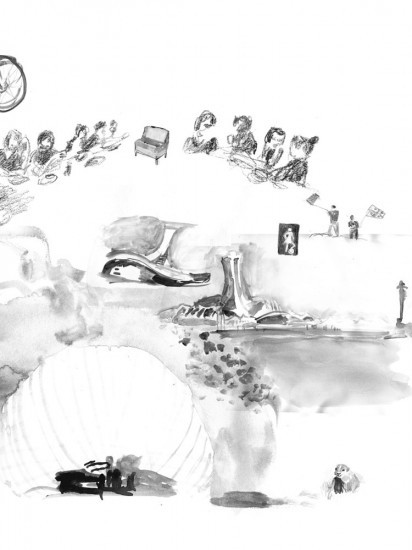

In its third year, 2006, DesignInquiry was extracted from its host, Maine College of Art, and test-run in a large farmhouse on the island of Vinalhaven with a smaller group of 22 attendees. Conceptually, this event was the most true to the ambitions of the program, to be participant- driven, seminar-like and non-hierarchical. As before, workshops and shift events were organized around a central topical issue, but each participant was invited to give a lecture presentation relating to the overall theme. The benefits of the more rural, nimble format seemed to outweigh the disadvantages: the sense that the event was a “retreat” helped refresh those of us who commonly default to rote techniques within the classroom or studio. The remote location might have been deterrent to prospective applicants, but by 2007, DesignInquiry was oversubscribed and applicants had to be turned away.

Underlying DesignInquiry’s push for a non-hierarchical learning environment is an implicit nod to the early education concept of proximal learning zones, whereby an unfamiliar setting and focus on a single, topical theme can in fact produce startling developmental progress or, in the professional world, innovation. The incorporation of practical issues, such as catering, into the design “problems” posed at DesignInquiry also aligns the event with recent developments in “relational aesthetics”—the term coined by art theorist Nicholas Bourriaud to describe art rooted in the notion of non-utopian, incremental improvements or deterritorializations of moments of everyday life. More important, preparing food, eating and cleaning can be non-hierarchical moments; particularly when ageing philosophers, famous designers, students and six year olds have an opportunity to discuss the ideas of the day. This, I think, is true design discourse. As Melle Hammer has noticed, it is in the nooks and crannies of the gathering —over dishes or out on the deck—that people have the chance to digest and share what they’ve experienced. So far so good. To conclude with Melle, DesignInquiry is not quite there yet: the experience is certainly there, but the next step is to care for the mission, to contribute to the interdisciplinary discourse of design through publication. This part is just beginning.