[Gabrielle Esperdy in collaboration with Anita Cooney]

Seven Strategies for Normative Architecture

It is conventional wisdom in architecture circles that only 10% of buildings are designed by architects, implying that the other 90% of buildings are not designed by architects.[1] This suggests an apparent lack of design intention, making that other 90%, in effect, designless.

These percentages are usually trotted out as a way of quantifying the degraded state of the built environment and qualifying the role architects might play in improving it.From a critical perspective, this interpretation of 90% of buildings is highly suspect, but it is not necessary here to refute either the implication of the pejorative or the impossibility of real designlessness, both of which I’ve done elsewhere.[2]

Rather, let’s consider that first 10%.While these are buildings in full possession of design intention, they are also engaged in a generally overlooked project of deliberate designlessness.This is not meant to equivocate, but these intentionally designed buildings do, in fact, participate in an architecture culture of the designless, one that emerged from a, heretofore, unexamined architecture practice of designing less.

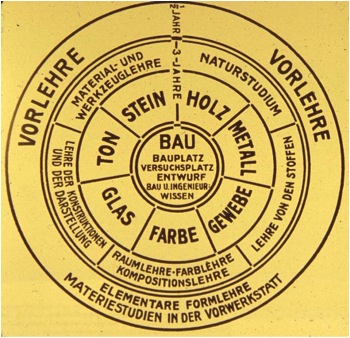

Though this practice became most pronounced in the 20th century, notably in the modernist pedagogy of the Bauhaus, it reaches forward to the 21st, in the protocols of Building Information Modeling.It also reaches backwards very nearly to the beginning of recorded history.

Retroactively identifying and analyzing the practice of designing less in architecture offers a means of reconsidering the evolution and continued relevance of normative architecture.In an essay from the late 1990s, Joan Ockman proposed “normative architecture” as a way of theorizing the hegemony of mid-century modernism and explaining how it was transformed by the dominant culture from socially radical ideology into socially palatable form making.[3] In other words, form making acceptable for conservative patronage, middling practice, and mainstream consumption—designing the 10% but influencing the 90%.

What follows extends the normative from theory to strategic practice and expands its chronological boundaries beyond modernism, from the ancient world to the information age, from Bau to BIM and beyond.

Strategy 1 Traditional Normative

The traditional normative designs less by rebuilding the same building.Intentions can range from the ritualistic and symbolic to the merely practical.

The Shinto Shrine at Ise in Japan is rebuilt every 20 years according to precise design specifications that were established at the end of the 7th century.The current shrine buildings, erected in 1993, are the 61st iteration of the tradition, which is intended to symbolize both impermanence and endurance. Gottfried Semper’s Opera House in Dresden was completed in 1841 and destroyed by fire in 1869; Semper rebuilt it with only minor modifications. The opera house was destroyed by fire again in 1945, the result of Allied bombing; the city rebuilt it as a stone-by-stone replica that paid homage to the glory of pre-war Dresden.A similar traditional normative impulse motivated those who called for rebuilding the Twin Towers after 9-11.

Strategy 2 Historical Normative

The historical normative designs less by designing the same thing over and over and over.From Paestum to the Parthenon, from Vitruvius to Vignola, from Palladio to Perrault, from Albert Speer to Leon Krier, classicism has been the most persistent form of the historical normative.For over twenty-five hundred years its canons and orders have defined the fine arts of architectural theory and practice, despite refinements of form, translations of material, and transformations of meaning.

In buildings across the millennia and across the planet, architects have deployed classical forms like the temple front, the triumphal arch, and the stoa with such regularity that is difficult to imagine a greater way to design less.

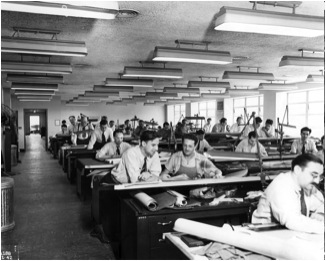

Strategy 3 Rational Normative

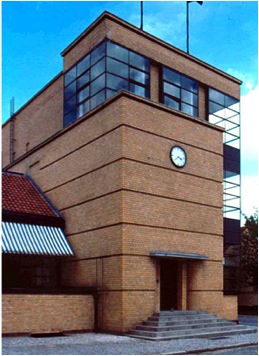

The rational normative designs less by claiming that all design decisions are based on function and utility rather than aesthetic preference.Subjectivity, individualization, and the artist architect give way to objectivity, standardization, and the technocrat architect.If the rational normative’s moment of triumph is the famous debate between Hermann Muthesius and Henri van de Velde at the 1914 Werkbund exhibition in Cologne, its vindication and possible denouement is the forms and ideas of the Bauhaus and its post-war progeny.Walter Gropius was perhaps its most ardent advocate, if not always its most faithful adherent.

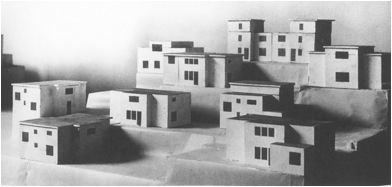

From his celebration of American industrial buildings, emulated in the Fagus Factory at Elfeld, to his Baukasten kit-of-parts system for mass-produced housing, to his heralded workshop block at the Dessau Bauhaus, Gropius championed what he called rationalization, arguing that “the vagaries of mere architectural caprice” had been replaced by “the dictates of structural logic.”Recognizing the architectural endgame this suggested, Gropius also promoted a Loosian belief in society’s aesthetic progress: “we have learned to seek concrete expression of the life of our epoch in clear and crisply simplified forms.”[4] Thus, the rational normative finds a social rationale.

Strategy 4 Generic Normative

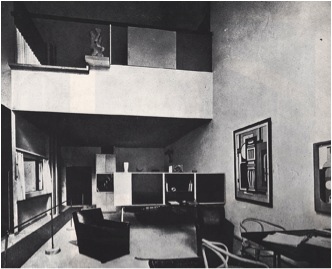

The generic normative designs less by fetishizing industrial and quotidian stuff while claiming it is merely specifying, not designing. Le Corbusier pioneered this strategy in the 1920s when he cast the objet-type, a universal and standardized object, as both an element and goal of architecture.

Whether specifying a Thonet bentwood chair in the Pavilion L’Esprit Nouveau or selling the Maison Citrohan as mass-produced machine for living, i.e. an objet-type at building scale, Corbusier idealized the generic as an appropriate norm for a century that saw the maturation of industrialization.

Progressive architects working in the U.S. before and after WWII were of a similar mind, believing that modern architecture must accommodate itself to advanced technology by willfully exploiting standardized products and processes.

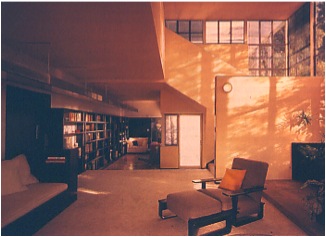

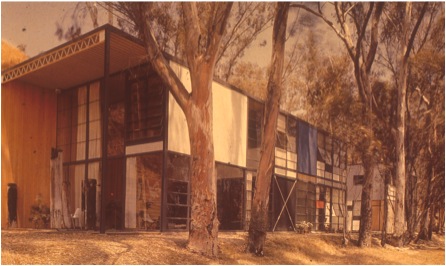

Richard Neutra and Charles and Ray Eames viewed the industrially produced building materials with almost talismanic regard:“Sweets Catalogue was the Holy Bible and Henry Ford the holy virgin.”[5] To this end, both the Lovell Health House and Case Study House #8 were full of generic, off-the-shelf components from steel frames and aluminum casements to fiberboard panels and automobile headlights.

In the 21st century, Muji represents the apotheosis of the generic normative.The company’s no brand brand wittily updates the objet type through a process of design distillation.From plastic pushpins to prefab houses Muji products are, as the company claims, simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary.[6]

Strategy 5 Artistic Normative

The artistic normative designs less by aestheticizing industrial and quotidian stuff while refusing to admit that it is customizing, not specifying.A key moment in the emergence of this strategy was the 1934 Machine Art show at the Museum of Modern Art.

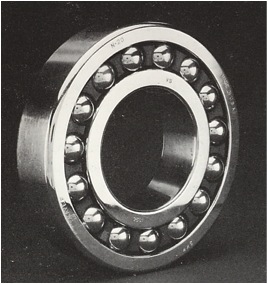

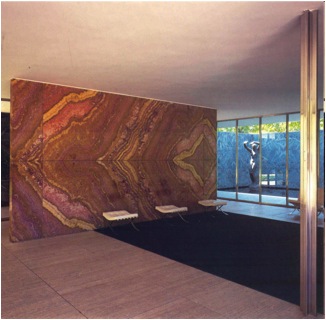

Though at first glance curator Phillip Johnson’s placement of factory made objects on MoMA pedestals appears to validate the generic normative, by elevating ball-bearings, propellers, and springs, as well as bathroom sinks, coffee urns, and desk lamps, into platonic ideals of abstract beauty Johnson was privileging appearance over function and aesthetics over use.Here, Johnson learned from his master, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Mies’ work from the 1920s through the 1960s, from the cruciform chrome plated steel columns of the Barcelona Pavilion to the bronzed I-beam mullions of the Seagram Building, epitomized industrially-derived elegance.

The artistic normative does not require such refinements of materials or methods.

Frank Gehry used cheap materials to great aesthetic effect in his early projects.In his own house in Santa Monica he transformed a modest mail-order type 1940s bungalow into a glorious one-off architectural pile, wrapping it with chain link fence, corrugated steel and plywood.Robert Venturi’s Fire House No. 4 in Columbus, Indiana is as precise in its details as the Seagram Building but the mannerism of its brickwork and massing is derived from the “ugly and ordinary” commercial strip.It is a dumb box, artistically considered.[7]

Strategy 6 Autonomous Normative

The autonomous normative designs less by claiming that all design decisions are based on an internal, hermetic discipline.Here, architecture suppresses such mundane concerns as program and function in order to prioritize generative and regulatory practices.The autonomous normative operates in both analogue and digital architectural realms, from Peter Eisenman’s paper houses of the 1970s to Greg Lynn’s blob houses of the late 90s and early oughts.

For Eisenman architectural autonomy, an exit strategy from the failed social project of modernism, produced a series of methodical, if not megalomaniacal, manipulations of a formalized grid.Intended as nothing more and nothing less than a visible record the design process, Houses I-X are architecturally dense in their layered and intersecting planes and humanistically empty in their begrudging accommodation to occupation.In Lynn’s work computational scripts and codes offer an even more rigorous application of the autonomous normative because parametric and algorithmic design has its own internal limits and controls.With its continuous surfaces and voluptuous forms, the computer-generated Embryological House has considerable sensual attractions. Whether it has social attractions of equal magnitude remains to be seen.

Strategy 7 Info-Normative

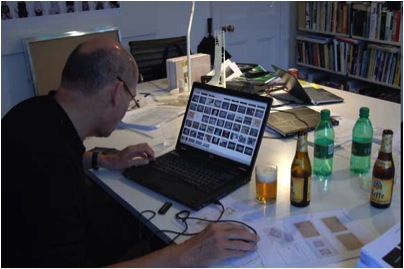

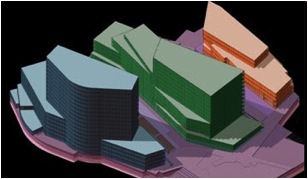

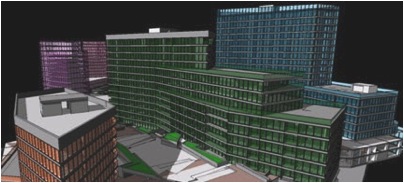

The info-normative designs less by claiming that data processing has replaced heroic design.

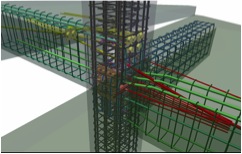

The preferred strategy of our supposedly post-industrial moment transforms the technocrat architect of the machine age into a data manager producing building information models that are integrated and life cyclical.Engineering, fabrication, construction, building systems, occupancy, and maintenance are rendered as a continuous stream of real-time data.This 3-D, born digital building information model is intended to replace the discreet and sequential development of conceptual and schematic designs, and design and as-built documentation, that characterized pre-BIM architectural practice.

At a basic level BIM is as apparently sachlich as the Bauhaus: only a handful of microchips separate the contemporary info-normative from the modernist rational-normative.The PC and the network retooled an earlier dream of factory-produced architecture, offering data exchange in place of the assembly line.Of course, data is rarely neutral and building information, like the tropes of function and utility it subsumed, is still subject to human contrivance—call it user error data corruption or user generated data mining, depending on your point of view.Either way, this is where the info-normative can create meaningful architecture, as evident in the Cooper Union Academic Building completed by Morphosis in 2009.

Here, as Thom Mayne has explained it, BIM was not a means of representation; it was a tool for thinking comprehensively and across disciplines in order to “build the thing itself.”[8] The strategy was not to consider form or structure or program or material or assembly or performance in isolation, but to take on all of them simultaneously as equally valuable bits and bytes of building information.In building the thing itself, the info-normative is triumphant.

*****

The traditional, historical, rational, generic, artistic, autonomous, and info-normative: these seven strategies for normative architecture are as prescriptive as they are ubiquitous.As this retroactive exegesis has shown, these seven strategies embody the designlessness of the intentional 10% of buildings.But their application in designing less might be a salve for the unintentional 90% as well.

[1] In the introduction to her recent history of architecture in the United States, Gwendolyn Wright discusses the “actors” responsible for shaping the built environment, observing that “Some are not architects at all, since professionals account for only about 10 per cent of what gets built in America.”The source of this percentage is not cited, indicating that it is general knowledge.See Gwendolyn Wright, USA, Modern Architectures in History (London: Reaktion Books, 2008), pp. 7-8.

[2] See Gabrielle Esperdy, “Less is More Again–A Manifesto,” Design Observer, 8 March 2009, DESIGNOBSERVER.COM.

[3] Joan Ockman, “Toward a Theory of Normative Architecture,” Architecture of the Everyday (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997), pp. 122-152.

[4] Walter Gropius, The New Architecture and the Bauhaus (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1965), pp. 38, 44.

[5] Harwell Hamilton Harris quoted in Esther McCoy, Vienna to Los Angeles: Two Journeys (Santa Monica: Arts + Architecture Press, 1979), p. 8.

[6] Muji, “About Muji: The Philosophy, What is Muji?” MUJI.US.

[7] For further ruminations on the dumb box see Gabrielle Esperdy & Anita Cooney, “Failings in Architecture,” DesignInquiry Journal, DESIGNINQUIRY.NET.

[8] Thom Mayne quoted in Bill Millard, “Mayne Challenges Performative Notions,” e-Occulus, 26 January 2010, AIANY.ORG.