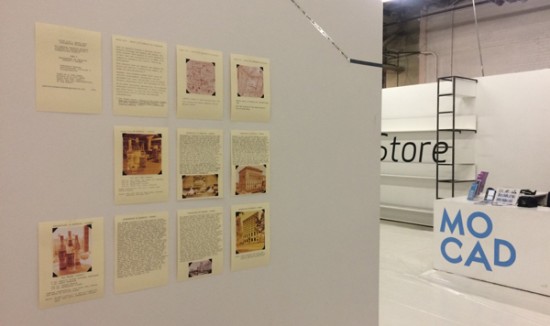

DesignInquiry’s Year of Agitation commenced with a follow-up to its DesignCities expedition to Detroit: a residency at MOCAD’s Department of Education and Public Engagement. The DEPE Space “enables adventurous, multidisciplinary programming in which the museum and city of Detroit function as sites for investigation and experimentation,” and that pretty much sums up the exploratory nature of DI and the DesignCities initiative. My own contribution is still very much a work in progress. As installed at MOCAD, the rawness of the thinking was reflected in the roughness of the presentation: a series of 10 typewritten cards, as in TYPED on a 1957 Halda portable with plenty of typos and, most likely, a few hasty conclusions to match.

This is research towards a colloquy between Detroit, Michigan and Newark, New Jersey, two urban centers (the largest in their respective states) that are cataclysmically in flux, with compelling parallels and equally compelling divergences. This research does not explore the reasons for crisis and decline in Detroit and Newark, as these are well documented [see Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (1996) and Kevin Mumford, Newark: Race, Rights, and Riots in America (2007)].

Instead, this research probes fault lines of rebirth, retrenchment, resurgence, and renaissance that have defined each city in recent decades, especially since the uprisings of 1967. As an urban ecological exploration, this research considers profound differences in urban identity and urban scale, of physical and cultural infrastructure, and of physical and cultural interventions.

The Last Word Cocktail

3/4 oz. gin [pref. Two James Old Cockney, made in Detroit]

3/4 oz. green Chartreuse

3/4 oz. maraschino liqueur [pref. Luxardo]

3/4 oz. fresh lime juice, strained

Shake ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled glass. According to tradition, this venerable drink was invented in the Grill Room of the Detroit Athletic Club at some point during Prohibition. With the privatizing of public drinking in the wake of the Volstead Act, members-only clubs like the DAC became a focal point for socializing while imbibing. And Detroit’s proximity to Canada meant the city was awash in bootleg liquor. Though some claim it was the rotgut quality of bathtub gin that required masking by the herbs and cherries of the mixers, there is no evidence to support this. Chartreuse, made by French monks since the eighteenth century, has always had a rarefied air. Maraschino may well have been produced locally back then, northern Michigan being a major cherry growing region. The origin of the cocktail’s name is lost to history though the drink’s potency (Chartreuse is 110 proof) is an obvious source. In the past decade, the Last Word has rebounded in popularity due to the craft cocktail movement. This recipe is based on one published in Imbibe, borrowed from mixologist Murray Stenson of Seattle’s Zig Zag Café, who discovered it in Ted Saucier’s 1951 book Bottoms Up.

Detroit Athletic Club Founded in 1887, the Detroit Athletic Club moved to its present downtown location in 1915. There, a block east of the Grand Circus, Albert Kahn designed an imposing, freestanding, six-story palazzo seemingly more appropriate for the Gilded Age than the Motor Age, but absolutely in keeping with the parvenu ambitions of Detroit’s new industrial elite. The building featured state-of-the-art facilities for sporting and socializing, including a swimming pool, a gymnasium, meeting rooms, and banquet halls. The Club’s original restaurant, the Grill Room, had room for more than 200 members who dined in neo-Renaissance splendor.

At the back of the Grill Room was the Club’s first and, until 1936, only bar, notable for its dark woodwork, vaulted ceiling, and a large saloon nude called Lilly (painted by Julius Rolshoven in 1900). Sensuous and mildly exotic, with just a hint of the louche, Lilly presided over the mixing of the first Last Word at some auspicious, gin-soaked moment between 1920 and 1933. The Detroit Athletic Club was restored in the 1990s; today it has more than 4,000 members.

The Newark Cocktail

2 oz. Laird’s Bonded Straight Apple Brandy

1 oz. sweet vermouth

¼ oz. Fernet Branca

¼ oz. maraschino liqueur [pref. Luxardo]

Combine ingredients, stir with ice, strain and serve in chilled glass. This early twenty-first century cocktail is a Jersey-accented variation on the Brooklyn, a drink that dates to the classic cocktail era (circa 1900), but has long been overshadowed by the inner borough’s iconic Manhattan. The Newark has no connection with New Jersey’s largest city, having been developed by two New York City barmen and served at their East Village speakeasy. They looked west across the Hudson and, even further, across the Meadowlands when naming the new drink because Laird’s has been making applejack, a.k.a. Jersey Lightening, in the Garden State since 1780. During the colonial era, applejack had a place in New Jersey culture that parallels that of bourbon in Kentucky: it was distilled and consumed in great quantities and was sometimes used as a currency in trade. According to tradition, George Washington himself asked Robert Laird to share his recipe for “cyder spirits.” That Newark never had a cocktail to call its own is not surprising: historically, it has always been in New York City’s outsized cultural and economic shadow. Even during Newark’s heyday as a manufacturing center, it frequently stamped its products with a “made in New York” label because Gotham’s marketing power was so much greater than its own. This recipe for the Newark is based on one published in Imbibe, borrowed from one developed by Jim Meehan and John Deragon of PDT.

Newark Athletic Club once stood on a prominent downtown location overlooking Military Park, a few blocks north of the city’s main commercial crossroads at Broad and Market. As designed by Jordan Green in 1923, the Club was a façade-oriented riff on the commercial palazzo typology that was as formulaic and routine as Kahn’s Detroit Athletic Club was robust. Though established in a moment of Roaring Twenties optimism, the Newark Athletic Club was bankrupt by the mid-40s, a victim of the Great Depression, which also caused the suicide of several of the club’s founding, businessmen members.

With 300 guest rooms, the Club was easily adapted for use as a hotel, and this transformation seems to have prompted a lobby refurbishment by Morris Lapidus. Though more restrained than the over-the-top eclecticism that would characterize his later work in Miami Beach, Lapidus’ design for the club-cum-hotel provided a modicum of swank and glamour—enough to imagine the lobby bar as the setting for the creation of a cocktail named for the city. Alas, this would remain a wishful fantasy: not even the Newark novels of Philip Roth make fictional mention of such an event. By the time a Newark cocktail appeared in a Manhattan cocktail lounge, the Newark Athletic Club had been abandoned, demolished, and replaced with the New Jersey Performing Arts Center. Though NJPAC has two different bars, neither serves a Newark, and recent efforts to order one in the city were met with polite incomprehension.

Note: This work also appears on American Road Trip.