Underneath the concrete

The dream is still alive

A hundred million lifetimes

A world that never dies

We live in the city of dreams

We drive on this highway of fire

Should we awake

And find it gone

Remember this, our favorite town

– “City of Dreams”

David Byrne, Talking Heads, True Stories

Cities are humans’ largest creative works. Cities have also been a creative muse from their first creation. Writers, artists and designers have wandered the cobblestone labyrinths of their memory and yearnings to call forth a dizzying variety of urban landscapes. Some of these territories are woven whole cloth from fantasy while others are shadow spaces that echo the actual built environments of history. Even those seemingly solid territories of “real” cities have some fantasy to their construction. A city is always more than its buildings and streets; it is also its stories, its energies, its ideas. Cities attract those who would build them higher and make them more by reflecting and projecting stories. You do not become who you are until you enter the city of your dreams.

In this essay, I examine three different designed objects [1] that provide striking metaphors for how we conceive of cities. I propose that these designed objects are interesting not solely for their aesthetic or physical qualities, but also for the way they indicate different conceptions of what a city is and what it is for. A designed object, like an art object, receives a subtle influence from the history and culture that wills it into being. A society that produces a design embeds that design with an array of implicit directions and meanings.

The cities that shaped and influenced these designed objects have a real historical existence. The city metaphors that we can draw from these designed objects are interesting not so much for how they provide a historical view of specific cities, though. Rather, the metaphors they provide suggest how we view cities universally and throughout time. This essay examines both how design creates cities through the creative work that gives shape to urban ideas and how cities create design by providing a rich environment for creative work.

City of Myth

The critical nature of cities as sites for human creativity and imagining is revealed in the primacy of the first city, Uruk, in the first story, the Epic of Gilgamesh. The Epic of Gilgamesh comes to us from fragments of preserved cuneiform writing found in what is present-day Iraq. While these fragments are incomplete, historians and archaeologists have been able to piece together a narrative for the epic from a variety of sources. Like Hercules or Cuchulainn after him, Gilgamesh was a wild force of nature, possessed of tremendous strength and vitality. He was renowned for his demonstrations of physical prowess and feats beyond the reach of mortal men. Within the Epic of Gilgamesh, however, Gilgamesh’s greatest accomplishment is the development of the great city of Uruk, capital of Ancient Mesopotamia.

Gilgamesh was both an active creator of the city of Uruk within the diegesis of the epic as well as a metaphorical shaper of the historical Uruk. The narrator of the epic proclaims that Gilgamesh wrote his own story on clay tablets entombed as a foundation stone in the walls of Uruk. This literal description likely hints at the importance of Gilgamesh not only to the physical existence of Uruk, but also to the identity of Uruk : Gilgamesh as a legend lends the city its stature in the world of Ancient Mesopotamia. It was his story that spread after his death and it was his story that survived to modern times; thus Uruk holds a unique place as the original city of history. Gilgamesh’s unique nature as half-human and half-divine provides us also with a creative metaphor for understanding cities. Cities hold sacred spaces that give physical form to eternal ideas.

From the beginning of the Epic of Gilgamesh the importance of Uruk to its people is made clear. The narrator will recount the great events of Gilgamesh’s life, but first the reader should be impressed with his most magnificent feat : the development of the great city of Uruk. The city is Gilgamesh’s greatest legacy. It’s place at the top of Gilgamesh’s listing of accomplishments suggests the critical and central place that cities held in the lives and imaginations of the Sumerians. The narrator asks the reader directly to consider this magnificent monument:

He built the rampart of Uruk-the-Sheepfold,

of holy Eanna, the sacred storehouse.

See its wall like a strand of wool,

view its parapet that none could copy!

Take the stairway of a bygone era,

draw near to Eanna, seat of Ishtar the Goddess,

that no later king could ever copy! [2]

Careful study of the city is suggested to the reader; one is asked to both “climb Uruk’s wall” and to “survey its foundations.” [3] That the details of construction are made explicit suggests great care given the technology of the time. The narrator asks : “Were [Uruk’s] bricks not fired in an oven?” [4]

The Hero Overpowering a Lion, Neo-Assyrian period, from the Palace of King Sargon II (721 BC – 705 BC), now located in The Louvre Museum. This style of statuary is often associated with Gilgamesh.

The Hero Overpowering a Lion, Neo-Assyrian period, from the Palace of King Sargon II (721 BC – 705 BC), now located in The Louvre Museum. This style of statuary is often associated with Gilgamesh.After surveying the accomplishment of the monumental city, the narrator describes the power and vitality that make Gilgamesh unique. As his great feats are listed, again the connection between Gilgamesh and his city is drawn tightly by proclaiming his role in “restoring the cult centres destroyed by the Deluge.” [5] Gilgamesh, both through his prowess and his careful cultivation of the urban landscape, had restored Uruk to order and prominence.

A more subtle reference to Gilgamesh’s importance to the life of Uruk and other Mesopotamian cities is found in the rising action of the story. The pivot upon which the narrative turns is Gilgamesh’s desire to sojourn forth with his friend Enkidu to slay the demon Humbaba and cut down the Sacred Cedar. While trees have been featured in other world mythologies, such as Yggdrasil in Norse mythology, the Sacred Cedar here may play a special role in our understanding of the importance of cities to Ancient Mesopotamians.

To best understand the role of the cedar in Gilgamesh’s pattern of urban development and cultivation, it is important to know that each city of this era had a patron deity. A ruler of a city or region in Ancient Mesopotamia was an agent of the gods and as such controlled the temple sites. [6] Sacred spaces were crucial to the Mesopotamians and were the physical center point of the urban landscape. Looking at the journey to retrieve the Sacred Cedar in this way establishes that, to a listener in Ancient Mesopotamia, the tree was not simply a totem of accomplishment for Gilgamesh. The tree’s role in the narrative was likely interwoven into the understanding of how critical Gilgamesh was to the creation of a proper city.

The retrieval of the Sacred Cedar by Gilgamesh was emblematic of his ongoing restoration of sacred spaces in Uruk and the other cities in his kingly domain. Trees, particularly larger mature trees, would have been prized components for building construction in Ancient Mesopotamia. The Sacred Cedar, as the “greatest” tree, would have been a jewel in the crown for building or restoring a city’s sacred spaces. Again, we see that Gilgamesh is renowned not just for his power, but also for his stewardship of the cities under his rule. To a listener in Ancient Mesopotamia, Gilgamesh’s encounter with Humbaba would have fit a pattern of Gilgamesh’s stewardship of cities under the rule of Uruk. That Gilgamesh took care to restore the city temples with prized materials would have been an esteemed element of his reputation as a proper and just ruler. For the ancient listener this characteristic would have also been foregrounded in the opening narration, wherein Gilgamesh is said to have “set in place for the people the rites of the cosmos.” [7]

The Uruk of Gilgamesh was a sacred space. While Sumerian writing, like many ancient myth texts, may strike the contemporary reader as descriptively bare, the presence of an evocative city pervades the text. Reading a passage such as Ninsun’s prayer for her son Gilgamesh, one imagines massive stone temples rising into the darkness among torch-lined streets which bring order to an arid plain. Gilgamesh’s lineage was unique; his father was human, his mother was divine. Uruk parallels his unique nature as the gateway between the mundane and the sacred.

As sacred spaces, cities frequently contain soaring monuments to our ancient past. These edifices serve, like Uruk, as a gateway between the quotidian nature of day-to-day existence and the eternal aspect of the greatest of human achievements. In contemporary cities, these sacred spaces embody a range of eternal ideas : knowledge is enshrined in the library, divinity is inscribed in the temple, justice is embedded in the court. These institutional fibers of a city’s fabric demand permanence; their eternal natures require that they are erected before we are born and that they will stand long after we die. The Epic of Gilgamesh is a story of the mortality of Gilgamesh and the immortality of his legend and the city it built. The epic also serves as a reminder of the power of sacred spaces and ideas. Gilgamesh, the leader, restored a great settlement. Gilgamesh, the legend, established a city for the ages.

City of Nostalgia

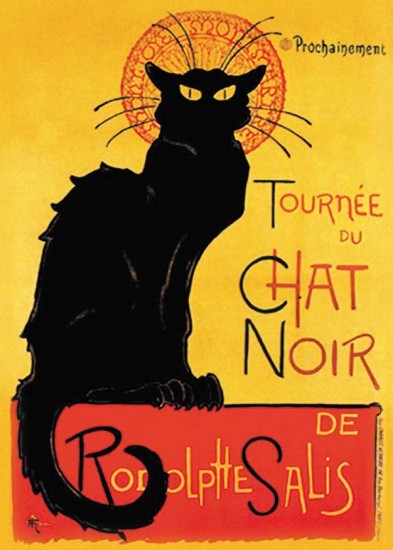

In the mid-1880s, Montmartre emerged as a creative epicenter for Parisian cultural life. The vibrant cabaret scene drew artists, writers, musicians and actors together into a bustling burst of creativity and innovation. Théophile Steinlen’s Chat Noir posters have become the emblematic graphic images of this fin-de-siecle Montmartre environment. The posters advertised Rodolphe Salis’ Le Chat Noir nightclub, one of the leading cabarets of the era. [8] Many of the images which celebrated Montmartre were created as critical, even salacious, depictions of urban life in Paris. Their mass re-reproduction as suburban status objects in our contemporary culture presents them as a nostalgic view of urban life. Montmartre is an archetypal example of the creative “scene”: the fertile urban environment that collects and encourages emerging creatives in the development of their craft. This view of a city is nostalgic because “scenes” by their nature are caught in a continual cycle of emergence, discovery and abandonment.

Montmartre creatives often referred to themselves as fumistes, a derivative of the French term for chimney sweeps, but which meant a person who took clever criticism of bourgeois society as a way of life. The fumisme attitude was one of sarcastic humor and satire meant to pierce the hypocrisy of the ruling elite. [9] Avant-garde French artists and writers were caught between a crumbling Republican France, with the defeat of Napoleon III and the end of the Second French Empire, and a rapidly emerging urban, international France with the increasing pace of industrialization. They rebelled against traditional culture, represented in fine art by the Academic painters who revered the forms and narratives of classical antiquity. The fumiste who were engaged in visual art were forerunners to many currents of avant garde 20th century art practices. Contemporary writers of the period were determined to introduce a keen naturalist voice into the literature of the day. The political and economic chaos of the era cultivated a powerful generative foment amongst the creative classes. The nearly absurdist fumisme perspective produced various artist groups, with nonsense names like the Hydropathes and the Incoherents. The membership of these groups often overlapped. They met in Montmartre cabarets, such as the Chat Noir or Quat’z Arts and developed both a thriving creative practice and lifestyle.

Steinlen was an active part of this avant garde Montmartre milieu. He was well-known amongst the artist community for his satirical illustrations, which were frequently produced under a synonym to escape reprisals from the censors. Steinlen’s simplified and stylized black cat from the iconic Chat Noir poster reflects another innovation of Montmartre creative nightlife: the use of silhouettes in shadow puppet theatre. The shadow puppet theatres were not only an engineering and aesthetic marvel, they provided a sanctioned platform for culturally sensitive and critical productions, such as Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. Puppet theatre’s role as spectacle and mass entertainment has often allowed it a special place in criticizing dominant cultural institutions.

The Chat Noir poster was not the only feline imagery Steinlen produced; his cat renderings were frequently featured in satirical publications of the day and fit into a larger milieu of detached, ironic cultural criticism known as fumisme. Steinlen developed drawings for the Chat Noir journal that were sketched in a proto-comic style with sequential panels telling a short, sardonic story of the titular black cat. [10] The narrative of each story presents the cat as a graphic stand-in for the fumisme creative. In these stories, the cat is a kind of anti-hero, like the fumisme artist. The black cat’s misadventures blend bad attitudes and bad luck in short vignettes that are clearly a form of gallows humor, but the connection exists between the ill-fated cat and the outcast Montmartre creative. Both make daring outbursts against their surroundings; both are met with rebuffs or calamity.

The Montmartre creatives were the first artists to work in an era of “l’art pour l’art” or “art for art’s sake.” Here, art was freed from the moral or edifying role that French Classical artists had yoked it with. Importantly for our considerations, art was freed from its social role. [11] L’art pour l’art allowed an art focused on the thoughts and desires of the individual artist. This begins to unlock the relevance of the Chat Noir and Montmartre avant garde to our conception of cities.

In this view, the city is a creative collector. It is a place where artists, writers and performers can congregate and, through collective activity, hone their creative practice to a highly experimental degree. Somewhat paradoxically, it is also a place where the creative practitioner can most fully explore an individual investigation. The artist in the urban environment can develop their unique perspective counter to the prevailing norms of society. The great material accumulation that is possible in cities can free the creative from the ordinary drudgery of survival. At its most extreme, the artist can literally live on the cast offs and in the waste spaces of an affluent urban society. The fumiste artists of the Montmartre milieu could only reject the hypocrisies of polite society from their own position of privilege. It takes the framework of a city to support such criticism.

The example of Le Chat Noir also demonstrates a nostalgia that takes hold in cities. Notably, by the time some of the iconic Montmartre advertising imagery was created, the creative life of Paris had shifted elsewhere. The images served as guides for tourists, rather than as enticements for the in-the-know creative Parisian. [12] Cities collect and catalyze creativity in bursts that flash and eventually fade. Montmartre and Le Chat Noir were a very early example, perhaps the first, of a trend that continues to this day, with the cyclical naming of new world cultural capitals, such as San Francisco in the 50s and 60s, New York in the 70s and 80s, Seattle in the 90s, Beijing in the 00s, Berlin in the future. [13] Although the reality of a Montmartre or Haight-Ashbury may include grinding poverty, substance abuse or social disease, the lens of nostalgia restricts our view to the romantic burst of creativity that such a setting engenders.

A city’s “scene” is always-already nostalgic, to borrow a Heideggerian phrase. The cutting edge of creative output in a city is always being discovered and discarded when the creative chaos of a city’s margins can only be “discovered” by the mainstreaming and civilizing forces of capital. Even as the cabaret scene was beginning its first flourish in Montmartre, disenfranchised fumiste were declaring that the Parisian rich who were flocking to be entertained were destroying the original spirit of the enterprise.

City of the End

Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira began life as a manga serialized and then collected in separate volumes by the major Japanese publisher Kodansha. Otomo oversaw the adaptation of the story into an animated form in 1988. [14] The anime shares with the manga an overall mood and aesthetic of a decaying, but dangerous future city riven by social strife. In each version, the narrative takes place in the technologically-developed but socially-dystopic future city of Neo-Tokyo. The image and role of Neo-Tokyo in the film reveals the final part of our urban metaphor, that a city is a site of great technological and social power and destruction. Neo-Tokyo itself is a monumental technological specter that haunts the film as well as a site for continual destruction and reconstruction, both of the physical and the social kind.

The narrative opens at a point that would seem to be an ending point : total destruction of Tokyo by a nuclear-level explosion. In the opening shot, a megaton blast rises up over the idyllic city like a black boil. The city is eclipsed in white light before the screen proceeds to a static-to-sharp resolution of a view from space. This shot slowly zooms in to the new Tokyo Bay, thirty years in the future. This new city is darker and more oppressive than our opening city. Neo-Tokyo has built up higher, denser and darker than before. The third shot, which presents the movie’s title, Akira, reveals the remains of Old Tokyo – a shadowed, blasted crater. These first three images place Neo-Tokyo at the center of the narrative of the film. Just as with Uruk and Montmartre, Neo-Tokyo as a city is as equally important a character as the humans and superhumans of the story.

The opening action reveals these human characters : the “Pills” biker gang, led by Shôtarô Kaneda. As Kaneda and his gang, including Tetsuo Shima, battle with a rival group, the “Clowns,” the new city of Neo-Tokyo repeatedly looms up over the action on the ground. The emphasis on the fast, dynamic movement of the motorcycles causes the city to literally loom as it rises up or sinks down while various characters execute high speed acrobatic battles across the blacktop. In static shots, Neo-Tokyo appears frequently as an iridescent background glimpsed between the crumbling foreground structures of the old city. The entire opening action happens at night. In this way, the old city and the new city are “all that there is,” as they fill the emptiness of night in each shot.

The contrast between the shining new city and the old city forms an important visual metaphor for one of the driving themes of the film : that the increasing social stratification of Neo-Tokyo (a proxy for 1980s Tokyo) is threatening to destroy the fabric of Japanese society. The two cities are frequently juxtaposed in several scenes of the movie, often in a single frame. The new city of Neo-Tokyo is rendered in jewel-toned blues, purples and golds that sparkle at the back of the frame like the City of Oz, while the Old City of Tokyo is colored in a set of bleak blacks and blues in the foreground. Old Tokyo is the reality of the film’s protagonist bikers. Neo-Tokyo is a rarely visited fantasy land. The color palette not only enforces a split between fantasy and reality, power and poverty, but it also establishes Neo-Tokyo as the seat of extreme technological power. The glittering windows, spotlights and mechanized advertisements of Neo-Tokyo contribute to the rainbow glamor of the city. The technology of Old Tokyo resides primarily in industrial machines, particularly the romanticized motorcycles of the rival gangs. This technology is older, grittier and less socially impressive than the shining facades of Neo-Tokyo.

Composite of three frames from the film Akira, 1988, Akira Committee Company Ltd., Bandai, Kodansha.

Initially it is the technology of commerce that sets Neo-Tokyo apart. As we delve deeper into the political intrigue of the film, however, a more elaborate level of technology divides the old and new city. After Tetsuo is captured by the military, he is tested for psychic powers by enormous detailed machinery that gives a glimpse of the scale of Neo-Tokyo’s technological development. Tetsuo’s comatose body is tilted forward and back in space by a Brobdingnagian MRI machine in a baroque display of technological force and elaboration. The scale of technological growth and encrustation in the film is due in part to its science fiction genre trappings, but the visual density of technology is also inescapably a critique of an increasingly mechanized Tokyo in the 1980s.

Colonel Shikishima is the film’s representative of Neo-Tokyo’s military forces. In his initial appearances, he is continually juxtaposed and identified with the new city of Neo-Tokyo and its entrenched interests. In one revealing scene, Shikishima is shown in his office discussing the machinations of the Japanese parliament. Here the forces of the new city are curiously allied with the traditional and the historic – Shikishima’s office features a large calligraphic painting and a formal bonsai tree. This transitions the viewer to considering another dimension of the destructive aspect of cities. The economic cycle of cities frequently entails a process of purposeful destruction of the old to create a new city tilted toward the elite. [15] Cities are built on a palimpsest of such cycles of destruction and clearing that promise rebirth.

Shikishima narrates his complicity in Old Tokyo’s destruction (and, by extension, the complicity of military and political elites) in a discussion with one of his scientific associates. As the floors of a Neo-Tokyo skyscraper flash by their elevator window, Shikishima relates “It’s taken thirty long years. We’ve come so far from the rubble.” He continues with his privileged point-of-view : “The passion to build has cooled and the joy of reconstruction forgotten and now it’s just a garbage heap made up of hedonistic fools.” The film sardonically presents the benighted perspective of the would-be rulers of Neo-Tokyo : after all of their hard work in destroying the city, through Akira, and then rebuilding it properly, they are repaid with “hedonistic” rabble who don’t appreciate their efforts. [16]

Just as the heightened technological power of Neo-Tokyo presents it as a city at the end of history, the fractious divisions within Neo- and Old Tokyo produce constant chaos. The normal social order is consistently shown as at least frayed if not completely tattered. The police and military act on fiat, the bureaucrats are consumed by their own bickering, the educational system combines brutality with cluelessness, the religious leaders stoke fear and violence in their followers. The only agents that can accomplish anything are the outcasts and fringe actors. Tetsuo prepares to destroy Neo-Tokyo with his emerging psychic strength while Kaneda, his biker gang friend, and Kei, the anti-government terrorist, are the only ones who can stand against him. Neo-Tokyo presents a city that is densely populated with a diverse and divided range of denizens and thus ripe for social destruction and disorder.

In this way, the destructive power of Neo-Tokyo lies not just in the pervasive technological trappings which threaten another atomic explosion, but also in the decayed social structure which pits every corner of society against the other. The final stage of the film sees (Neo-) Tokyo leveled once again, with only a faint ray of hope for its future. This slim hope appears literally as thin shafts of sunlight slicing down through the ruined city, but also metaphorically in the figure of Kaneda who stops Tetsuo not through violence, but by reminding him of their common friendship. As a balancing point to the film’s teetering social dynamics, it is instructive that one of the most prominent stickers on Kaneda’s bike when he arrives to confront Tetsuo reads “Citizen.” Cities, like Neo-Tokyo contain two great destructive potentialities : tremendous technological power and divided populations.

Conclusion

Cities are much more than vast physical networks. Cities embody our principles of how to live with each other. The three cities that feature prominently in these selected design objects each present a different facet to these principles. Uruk envisions cities as sacred spaces that enshrine our mythological aspirations. Montmartre provides a window onto a nostalgic city of combustible creativity. Neo-Tokyo cautions us against the underside of cities’ seemingly limitless potential by foreshadowing the dangers of overwhelming technology and social strife. These aspects provide a lens with which to view other cities in our contemporary times.

In this essay, I have only made the beginnings of some comparisons, such as between Montmartre and contemporary Berlin. Other connections could certainly be fruitful to draw. As of this writing, political uprisings have sparked across the Middle East. In Cairo, volunteers strove to preserve ancient Egyptian artifacts from looters, recognizing the power of the sacred and mythological in their city. In Tripoli, Colonel Qadaffi’s mercenaries attacked peaceful demonstrators in a reminder of the fragility of a city’s, and nation’s, social order, as well as the power of destructive technology to obliterate that order.

Tahrir Square, the site of the Egyptian protests which galvanized progressives in the Spring of 2011, may allow us to leave this discussion of cities on an optimistic note. The site is humble. It’s function before the protests was primarily as a traffic circle. [17] While there are monuments there, and important institutions, such as the Egyptian Museum, the majority of Cairo residents likely saw it, prior to the demonstrations, as a place to pass through on the way to somewhere else. Yet, it’s re-conversion into a site of revolutionary protest transformed this ordinary apparatus of a city into a site that will hopefully have importance for generations to come. In this way, the single site of Tahrir Square may encompass many or all of the urban characteristics we have considered : sacred spaces, creative ferment and social upheaval.

_________________________________________________________________

NOTES

[1] I want to use a broad sense of what is designed and what counts as a “design object” so that we might draw from some interesting examples of human creativity and planned thinking. So, in this essay, I am describing designed objects that are instances of the use of metaphor to communicate an idea.

[2] “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” translated by Andrew George, Penguin Books Limited, London, 2003. Pg. 1.

[3] Ibid., Pg. 2.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., The Deluge mentioned here is described later in the epic and is similar in nature to the Old Testament flood.

[6] “Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East,” by Michael Roaf, Andromeda Oxford Limited, Oxfordshire, England, 2003. Pg. 74, 76, 83. An extended discussion of the interconnections between rulers, religion and city life is found throughout the second chapter, entitled “Cities.”

[7] “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” Pg. 2.

[8] “The Spirit of Montmartre : Cabarets, Humor, and the Avant-Garde, 1875-1905,” Edited by Phillip Dennis Cate and Mary Shaw, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Pg. 23. From the essay “The Spirit of Montmartre” by Phillip Dennis Cate, which opens the catalog.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “The Spirit of Montmartre,” pg. 35

[11] The social role is the one art would have during the time of Uruk : to reinforce the institutions of religion or the king.

[12] Guide de l’étranger à Montmartre, produced in 1900, is one such example with its cover by Jules Grun. Notably, the preface to the guide was written by Emile Goudeau, who declared the Montmartre essentially “sold out” in 1885, when it had scarcely begun. “The Spirit of Montmartre,” pg. 38-39.

[13] Cities often hop on and off this list. Weimar Berlin was perhaps the capital of creative energy in the 20s and early 30s.

[14] “Manga : Sixty Years of Japanese Comics,” by Paul Gravett, Harper Collins, New York, New York. Pg. 108-109.

[15] This idea, and its significance in Akira, is elaborated at greater length in “Born of Trauma: Akira and Capitalist Modes of Destruction” by Thomas Lamarre.

[16] Lamarre nicely links this point of view to the “disaster capital” adventures of the Bush administration. Certainly, Shikishima’s disgust echoes the Neoconservative belief that American soldiers would be greeted in Iraq as heroes and liberators.